We’re big fans of gender-reversal experiments and projects, because they challenge stereotypical perceptions when it comes to defining men and women in their social capacities. In particular, they can dismantle harmful ideas that disproportionately affect women. In Hollywood there have been a number of women speaking about playing famous roles (Sigourney Weaver as Ripley in ‘Alien’ and Sandra Bullock in ‘Our Brand is Crisis’) that were originally written for men, but when played by a woman they proved certain character traits or archetypes shouldn’t be seen as “male” by default.

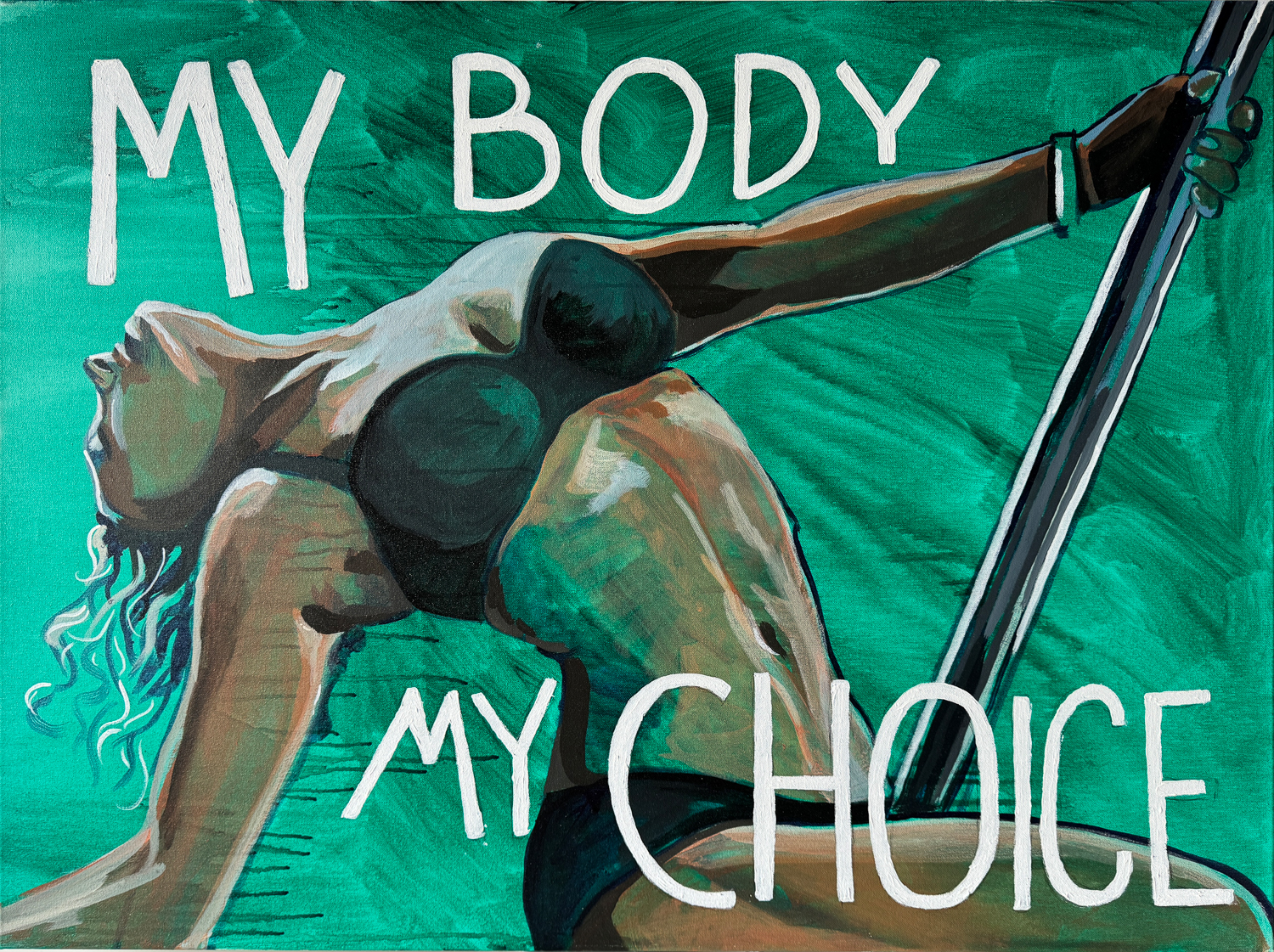

This translates to so many areas of life, and one artist has used her creative skills and passion to show exactly how. Felice House is an associate professor of painting at Texas A&M University, who originally hails from Massachusetts. When she moved to the Lone Star state, she says there was an initial culture shock, but she soon fell in love with her new home, and one aspect of it in particular – the “Western” culture.

But after watching a lot of the classic Hollywood Western movies, she started to get annoyed at one aspect that was common among most of them: “I was horrified by the roles for … anybody except white men basically,” she told Upworthy.

So she decided paint a series of the classic cowboy characters played by the likes of John Wayne, James Dean, Clint Eastwood etc, and give them a female reboot. Since she had already embarked on artistic projects that portrayed women in contrast to the way they are stereotypically and narrowly portrayed in the mainstream, combining her new love of Western culture and her artistic skills became the ‘Re-Western’ painting series. She put out a call for models and had a lot of women respond.

We spoke with Felice about her painting series, why she felt it was important to change up the old Western image, and working with the girls she chose.

Tell us about your artist background and how it became part of your studies.

My mother is a drawer/painter. She worked out of a studio in our house when I was growing up and took me to her life drawing classes. So it is not surprising that when I walked into my first painting class at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, holding a box of my mother’s old oil paints, I felt like I had gone home.

My father has been in the field of computer graphics since before it existed. He is a professor. I am also a professor teaching at Texas A&M University’s Visualization Lab In this capacity I work alongside computer scientists (like my dad) and other traditional artists (like my mom) to impart a range of skills that lead students into the fields of animation, gaming and more traditional art practices. To put it simply, the apple didn’t fall far from the tree.

What was it about Western culture that had you so infatuated, when you moved to Texas?

When Andy Warhol chose to represent Elvis, he did so in a classic cowboy pose. There is just something ‘All American’ about the idea of the cowboy. The archetype has a renegade flare that is hard not to fall in love with. And yet, it is highly problematic in terms of both race and gender. My thought in creating the Re-Western series was to take the captivating aspects of the archetype and use it to talk about gender and power in culture.

You are passionate about examining the representation of women in media, can you talk to us about why this is important to you?

The Guerilla Girls’ artwork tells the story more clearly than I can, “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female”.

For centuries men have created paintings of women for a male audience. Today women have access to training and education and are creating images of women that more fully represent our lives and experiences. The Women Painting Women movement has been an important tool in highlighting female artists working in the figurative tradition. We have come a long way. And there is a long way to go.

Can you explain some of the culture shock moving from Massachusetts to Texas?

Williamstown, Massachusetts where I spent my third– ninth grades, was the epitome of a quaint east coast private college town. Being the home of the Clark Art Museum and the Williamstown Theater festival, it had a lot to offer in terms of culture. It was manicured and regulated.

Texas, in comparison, was the wild west. There are abandoned downtowns, miles of nothing, enormous pick-up trucks and a visible gun culture. At first, I was really in shock. I began to fall in love with Texas when I became friends with kids who lived in the country. I quickly realized there is nothing sweeter than sitting on a hay bale watching cows eat, swimming in tank ponds and climbing on pump jacks (the Texas seesaw).

What were some of the observations you made about the female characters in Western movies, and why did you decide to use your art to subvert to these tropes?

As far as I can tell, there are three main roles for women in western movies: ‘the hooker with the heart of gold’, ‘the waiting wife/girlfriend’, and ‘the damsel in distress’. I have no interest in any of these roles….. I am sure you can understand. Since the genre is so integral to the American identity, I figured it was my job to make it accessible to all.

How did the idea for your series come about?

The original idea was to make a series of powerful cowgirls. But when I started photographing models, the images were not conveying the strength that I wanted. It seems that the cowgirl archetype has been hypersexualized in culture – google ‘cowgirl’ if you don’t believe me.

I was about to give up hope, when, during a Photoshop sketch session, I put one of my model’s heads on John Wayne’s body. It was so funny and right. The ‘gender flip’ pointed to the gender power disparity in culture. It was at that moment that Re-Western was born.

What are some of the main messages you want people to take away from these paintings?

This Baha’i quote has been instrumental in shaping my views about gender, “The world of humanity has two wings—one is women and the other men, not until both wings are equally developed can the bird fly. Should one wing remain weak, flight is impossible.”

I want the viewers of Re-Western to recognize that for gender equality to be realized, men must consciously hand over the powerful roles that have been assigned to them and women must courageously step into them.

Can you share some of the most surprising feedback you have received so far?

The best feedback came from the models themselves. We worked together during photoshoots to figure out how to make aloof, uncaring facial expressions. Since women are trained to be coy, approachable and friendly, consciously not doing this that was surprisingly empowering.

This is an amazing article written by Virginia Schmidt about her experience becoming Virginia Eastwood. Here is an excerpt:

“Felice has made quite a timeless, fearless, and culturally/socially radical go with her Re-Western exhibit, sharing it with the world as she has reimagined females in classic male cowboy roles, questioning ‘gender stereotypes and access of women to power.’ I was lucky enough to be painted into cowboy history forever times three by Felice, starring as Virginia Eastwood, Virginia Wayne, and Virginia Banderas in powerfully feminine reimaginings of iconic cinematic cowboy moments.”

Why did you decide to make these paintings so large?

In order to talk about culture’s relationship to women and power I needed the viewer to look up to, and being dwarfed by, these women. This strategy of using scale to heighten the power of the subject and has been employed in portraiture of kings and military rulers for centuries; think Napoleon.

With gender equality and sexism being talked about a lot, especially in politics right now, how do you hope to contribute to the discussion, and challenge negative perceptions with your work?

“Tomorrow hopes we learned something from yesterday.” – John Wayne.