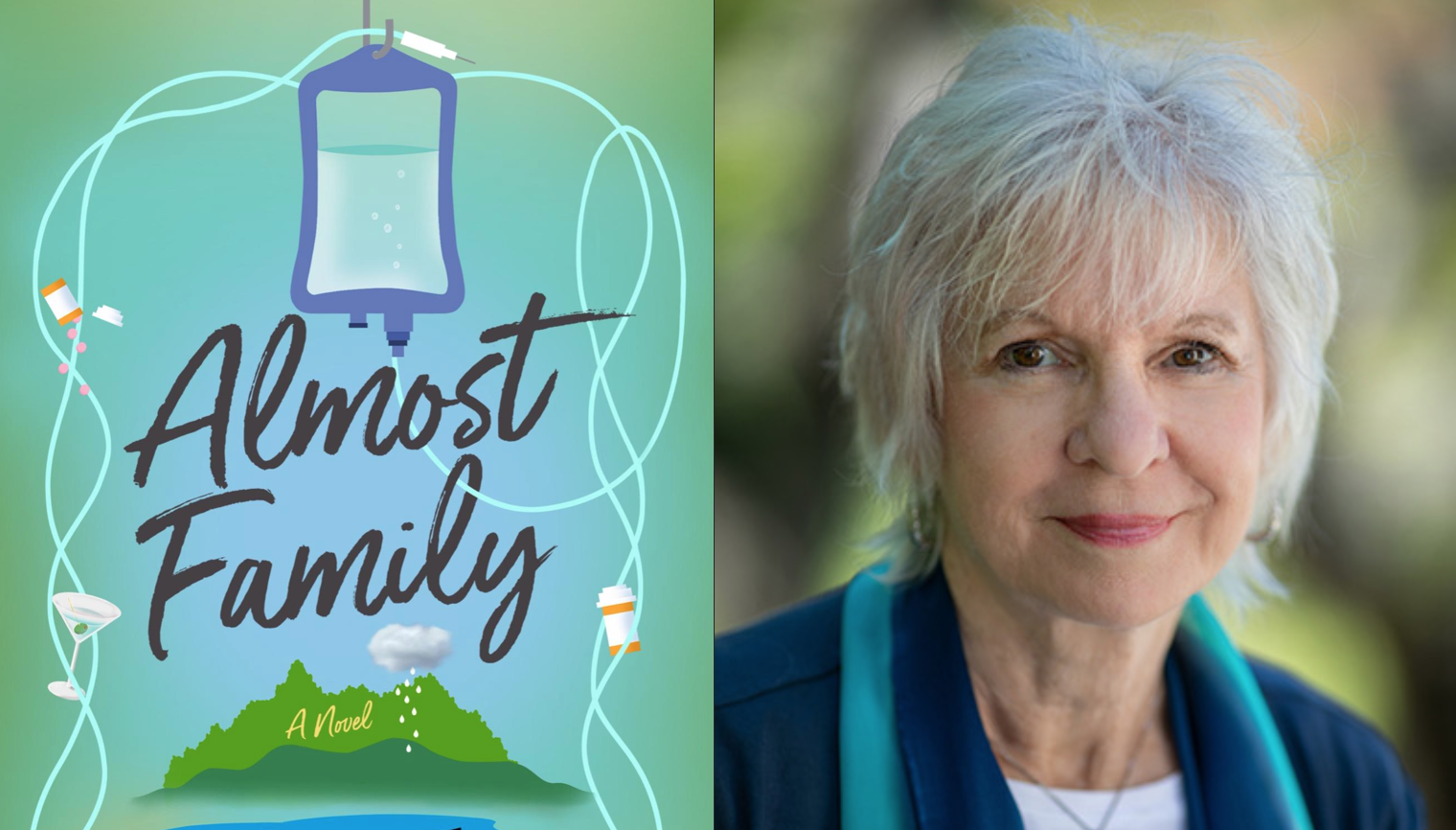

By Donna Levin

‘He Could Be Another Bill Gates’, my latest novel, journeyed a long, tortuous route from idea to printed page.

Forget Sasquatch and the Loch Ness monster. The most haunting legend of our time is the book that “wrote itself.” People know someone who claimed, “my novel just flowed right out of me!” But these reports, suspiciously enough, are always at one remove, or more. They’re like near-death experiences: Until it happens to you, it’s entirely a matter of faith that it’s possible.

It sure happens frequently in made-for-cable movies: the writer is blocked; she takes long walks on the beach, usually at sunset; she drinks heavily; she fights with her partner. But then she recovers a memory, often having to do with a family secret, and in the next frame she’s signing hardcovers.

There probably are the occasional books (and stories, and poems) that seem, miraculously, to write themselves. And we writers launch new projects hoping that this will be the easy one. It’s like buying lottery tickets. A girl can dream. My previous novel, ‘There’s More Than One Way Home’, was in part a retelling of ‘Anna Karenina’. In the end (spoiler alert), my Anna doesn’t commit suicide, but finds herself a single mom with two children.

I didn’t consider it a mystery in the genre sense. But in the beginning a boy falls to his death, and Jack, Anna’s ten-year-old year son on the autism spectrum, is accused of causing the accident. We don’t learn what really happened until the end.

For some reason, I have it in my head that it was F. Scott Fitzgerald who said, “every good novel is a mystery,” but in spite of relentless googling I have not been able to confirm that. So it may be that, like Ann Herbert’s “practice random acts of kindness,” it is now an aphorism that belongs to the world.

When I wrote ‘California Street’, my second novel, I had read approximately three mysteries in my entire life, and that included ‘The Mystery of the Missing Goat’ in third grade. Shortly before ‘California Street’ was published, I got a call from my editor at Simon and Schuster: She told me that the Mystery Guild had chosen the novel as an alternate selection.

I thought of that old, misogynistic joke: “ambivalence is watching your mother-in-law drive of a cliff in your new Cadillac.” Today it would a Porsche—but I digress. This was good news, but I was afraid that mystery readers would be disappointed in the plot of my novel, which was about as twisty-and-turny as the street for which it is named. (California Street has some hills, like most San Francisco streets, but it is otherwise nearly ruler-straight for five miles.)

But the publisher knew what they were doing.

When people asked me about ‘California Street’ and I (hesitantly) replied, “it’s a mystery,” they universally exclaimed, “I love mysteries!” By contrast, when my first novel was published and people (baristas, doctors, acquaintances, and joggers I managed to overtake) asked me what kind of book it was, I struck a pose with an invisible cigarette and said, “literary fiction.” They said, “oh.”

Which is how I discovered just how much readers love mysteries. If publishers put “a mystery by James Joyce,” on the cover of Finnegan’s Wake it would fly off the shelves, and readers would shake their heads saying, “I did not see that coming,” about the end.

I think one of the attractions of the mystery genre is that readers are reassured that even if they don’t get a clover-leaf plot, they will not be marched through a hundred pages of a woman slicing zucchini in her kitchen while reflecting upon, and, of course, coming to terms with, her life.

So it was that after I completed ‘There’s More Than One Way Home’, I had the idea that I would write a trilogy—maybe even a series!—of novels in which Jack, the boy on the autism spectrum with an eye for detail, solves mysteries. After all, he had provided the crucial piece of information that explained the boy’s death in ‘There’s More Than One Way Home’.

In each book, Jack would be older, and the stories of the characters around him would evolve accordingly.

This territory has been mined by authors such as William Bernhardt, with his fictional autistic savant character, Darcy O’Bannon, and Alexei Maxim Russell, whose ‘Trueman Bradley Aspie Detective’ series has a cult following. But all territory has been mined. Some Sherlock Holmes fans believe that he was on the spectrum.

A little knowledge, however, can be a self-sabotaging thing. By this time, I’d read many mysteries, and I didn’t trust myself to stumble onto a plot that would satisfy readers, the way I had with ‘California Street’. I mean those gratifying moments when you gasp, “I knew it! I mean, I should have known it! Tigers don’t live in Africa—they live in India!”

Could I learn? Maybe.

In my original vision for ‘He Could Be Another Bill Gates’, Jack, is now sixteen and he becomes infatuated—no, that’s condescending—he falls in love with a copper-haired beauty named Ashleigh. She disappears at the beginning of the book, and that triggers the “mystery.”

But then, if she’s gone, how do I explore their relationship? Okay, then, let her disappear later in the book. But then… how is it a mystery? A prologue! A prologue in which we learn that she will be missing!

But, “You don’t need this prologue.”

That was the consensus of my writing group without whom I would still be wandering in the desert. The conventional wisdom has it that women are less likely to ask for help, and I believe that’s true, for example, when it comes to sharing household chores (my solution in this area is simply to leave the household chores undone), but it is not true when it comes to writing fiction. Writing classes are usually dominated by women. So are writing groups.

These eight women gave me unqualified support, but unqualified support does not equal, “Oooh, I love it. Let’s open another bottle of Pinot Blanc.” It means, “We believe in you, and you don’t need this prologue.”

And harder truths as well: “Anna is very angry,” one woman said of the heroine-mom. “I need a reason to like her.”

They turned my compass north again. What I wanted most of all was to be in Jack’s head as he comes of age and falls in love, and to be in Anna’s head as she learns to trust again. I had to learn to trust my own process again. I set myself the goal of writing a minimum of 1000 words a day, creating any situation that involved my characters.

With the support and encouragement, but above all, the incredible patience required of these women to listen to these sometimes-random excerpts, I wrote 60,000 words, most of which survive only on my hard drive. The novel not only did not write itself, it was more challenging that any other I had written. By the time I’d written 60,000 “extraneous” words I could see the plot in its entirety: The subplots began to reach into one another and wove a tapestry in which Anna, Jack, Ashleigh, as well as Anna’s ex-husband and new lover all had a stake in the outcome of one another’s stories. (The final version is a little over 100,000 words.)

During the time I was writing ‘He Could Be Another Bill Gates’, two other women finished and are now publishing their novels. The others have novels, or memoirs, in progress. I’ve done my best to give them the support as well as the hard truths. Before I met them, I did not believe such women existed, and learning that they do is as valuable as anything else they gave me.

Donna Levin is the author of four novels, including He Could Be Another Bill Gates, publishing in October, 2018 by Chickadee Prince Books. She lives in San Francisco.

2 thoughts on “Author Donna Levin Says The Secret To Her Success Is Her Community Of Female Writers”