By Natalie Bickel

I stepped foot into my 91-year-old grandmother’s patio home in March of 2021, the room suddenly feeling reminiscent of Christmas. My aunts were in town, which usually happens around the holidays, but, like many things, the 2020 pandemic broke tradition. Here we all were – gathered around in the spring instead of December. I noticed a pile of items stacked on the fireplace planned for donation. My aunt, her middle child and spitting image at five-foot-even, picked up a small leatherbound book, just barely larger than a wallet with the word “Autographs” imprinted across the front.

She began to read entries from classmates, each one dated in the upper-righthand corner with the year 1943, written during the height of the US involvement in WWII. The pencil-scrawled words were mostly from female classmates notating the end of a school year with my grandmother moving on from a high school freshman to a sophomore, referring to her on multiple occasions as a “cute girl” and “flirty freshman.”

Dear Bodie,

Do you love me or do you not? You told me once but I forgot.

Always,

Bett

P.S. From a silly sophomore to a flirty freshman.

—

Dear Bodie,

To a cute girl and a swell kid.

A Friend,

Anne

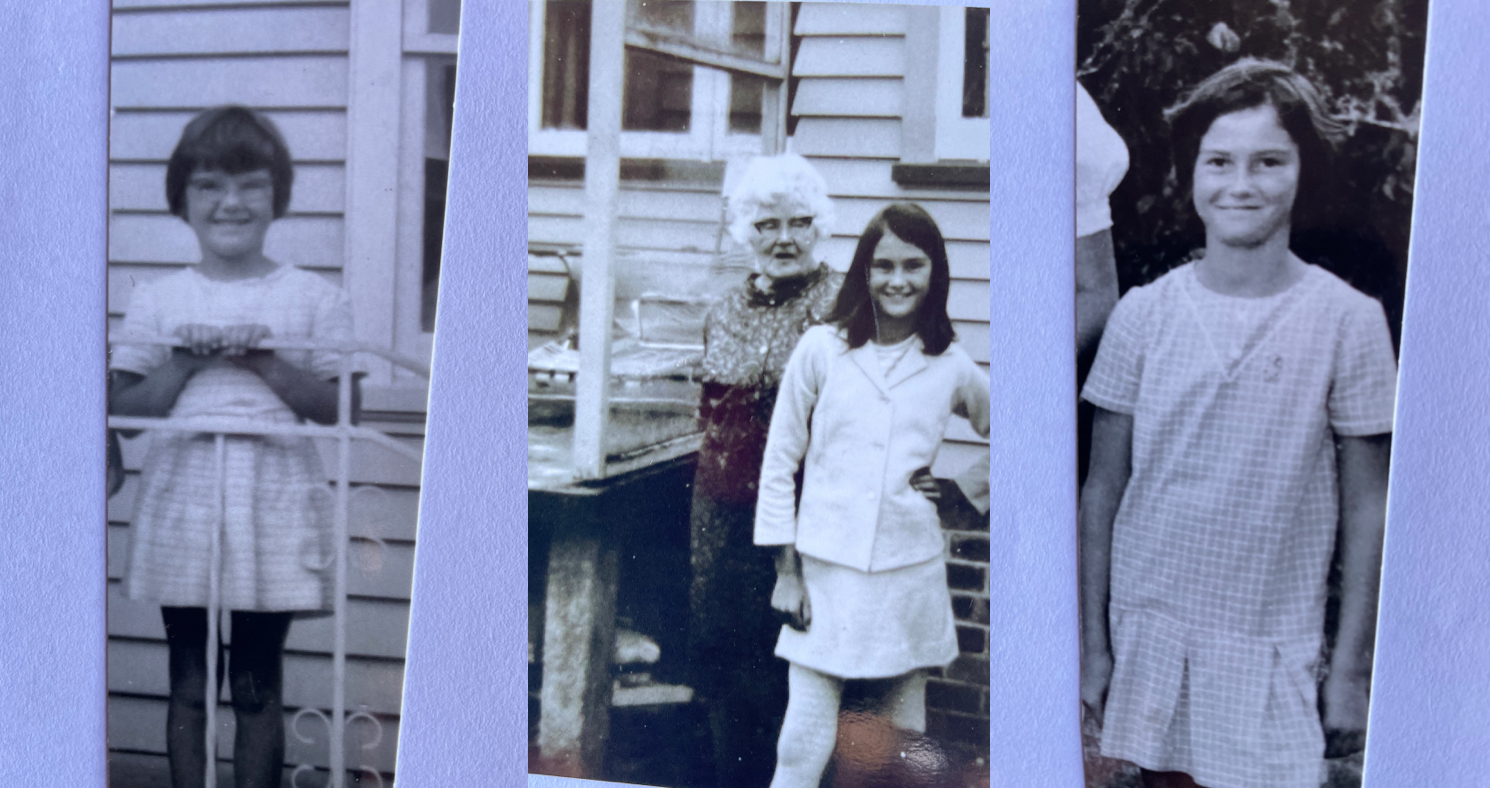

I watched my grandmother, Bodie, as her classmates knew her, sit back and listen to the clever poems, charming verses, and rhyming notes her friends took the time to write down for her. I could tell she was trying her best to think back to those days, to remember who those friends were during that time of her life. This is a woman who has lived through 17 presidents, World War II, and now two pandemics. She’s a woman who has outlived two husbands, who has protected and united her family time and time again, and ultimately exemplifies the truest definition of a matriarch.

To watch Bodie, a woman with an overflowing backlog of lived experiences, reminisce about this simple time in her life felt almost impossible. Yet, we had all been forced into a shutdown world of simplicity during the seemingly impossible year of 2020.

As my aunt continued to read through the yearbook-style entries, we chuckled at the flowery language they used. Themes began to emerge reflecting traditional women’s roles at the time including cooking, sewing, and having children, paired with the longing to be remembered exemplified in “forget-me-not” closings. Situational phrases of “come running” and “set a plate for me” embodied the commitments to lasting friendships while the repeat subject matters of rationing sugar and safety pins dated the book, a testament to wartime.

Bodie,

‘Tis sweet to kiss, but oh how better to kiss the lips of a tobacco spitter.

Mac

—

Dear Bodie,

Roses are red

Violets are blue

Sugar is rationed

And so are you

A Freshman, Gene

—

Dear Bodie,

When you get married and have twins, don’t come to me for safety pins.

A Friend,

Jimmy Jolly Jr.

During the 1940s, my grandmother remembers participating in several drives where she collected papers, specifically newspapers, and metal products that were then sent to the government where they were recycled for the war. Bodie’s family also bought 25 cent savings stamps in efforts to fill a book which equated to a savings bond of $18.75 at the time.

With war efforts top of mind, priorities shifted, coming to fruition in the form of rationing with shortages in sugar and shoes. At least, for Bodie, those were the items that surfaced from her expansive memory. The thought of rationing sugar, an overstocked item at grocery stores today, struck me. It took me back to the onset of the pandemic with visions of consecutively empty aisles and the longing for toilet paper instantly rushing back.

Safety pins also seem like a silly item to worry about, but then, so did toilet paper, until we no longer had it. Our current situation probably felt somewhat like déjà vu for my grandmother, with COVID-19, infiltrated with unknowns like a war, provoking seemingly unending fear. The simulation of finding out your loved ones have been injured and struck down, fighting the battle to live while those back home pooled resources together to make it through were all too familiar for her. I pondered this as I turned my attention back to the notes being read.

Dear Bodie,

Times are hard, boys are plenty. Don’t get married before you’re 20.

A Friend,

Jeanne

—

Dear Bodie,

Remember me early,

Remember me late,

Remember me at supper time,

And set me a dinner plate.

A Pal,

Joanna

One was written solely in shorthand, a method used specifically for dictation and notetaking at the time. Now it feels more like a secret code, a lost language that, unfortunately, none of my family that was present could decipher. The brevity, yet complexive nature of it was remarkable, making modern texting abbreviations seem rather lazy compared to this historical creative artform.

Dear Bodie,

I wish you luck

I wish you joy

I wish you first a baby boy

When his hair begins to curl

I wish you then a baby girl

And when her hair grows long and thin

I wish you then a set of twins.

Your girlfriend,

Alice

—

Dear Bodie,

When I am dead and almost rotten,

Please think of me and come a’ trottin’

An S.H.S. Pal,

Marietta

Another rhyme ended with the line “God made girls for boys to squeeze.” While most of the poetic inscriptions seemed clever and harmless, each one reflected a cultural norm of the time. I listened as that particular one was read, uncomfortable that the words from 1943 did not conform to the social standards of today. From the recent Me Too Movement, to former president, Donald Trump’s sexual misconduct, to the former USA Olympic Gymnastics Coach, Larry Nassar’s sexual abuse cases, and many more veiled and unveiled assaults, I realized we’re starting to make progress in exposing the dishonorable. While these terribly corrupt actions are still happening, our culture is no longer tolerating them, causing many to rise up in bravery with hopes that these injustices continue to decrease as we progress.

My thoughts then expanded to an aerial view of that time period and the overarching idea of autographs, the basic differences of their connotation from then to now; how symbols of identity, such as signet rings, used to be a way of imprinting initials rather than existing as vintage jewelry, and how signatures at their core, no matter the decade, add an untouchable level of trust, value, and ultimately power.

Back then, a booklet with the word “Autograph” across the front symbolized well-meaning words from familiar friends. Before my aunt opened the book, I immediately thought my grandmother had collected signatures from renowned people and stars from her youth, as autograph books of today are simply filled with names, maybe a brief note if you’re lucky, from celebrities, and typically possess some sort of monetary value.

Dear Bodie,

When you get married and live by the lake,

Send me a piece of your wedding cake.

Your friend,

Ruth

—

Dear Bodie,

When you get married and live on the hill

Please send me a note by the Whippoorwill.

Your Classmate,

Duke

I felt conflicted while looking at Bodie’s tiny, tattered book with the question of which we should value more – the clever words of our friends, or the well-known names of those in our culture? The past year has inspired me to rethink a handful of normalcies we’ve created and the patterns of our country.

I’m appreciative I’ve had the time to sit in the silence to now be sitting in the same room with my grandmother. I’m unbelievably grateful that I didn’t have to say goodbye to her in the last year, like many others had to with their beloved family members. At the close of each note, alongside the signatures were simple notes of forever-type sayings, composed in impossible riddles.

Yours till the catfish has kittens.

Yours till Germany gets Hungary and eats Turkey fried in Greece.

Yours till the ocean wears rubber pants to keep its bottom dry.

As the last entry was read, my grandmother smiled, enjoying the transient travel to a simpler time in her life. It made me appreciate the ways of the past, how pieces of it were mirrored in 2020. During a war, young people found a way to laugh, love, and connect. They did what they could to serve one another, while partaking in the few simple, yet joy-filled experiences they still had, including going to the movies and watching musicals, giving the nation a much needed uplift.

We adapted through the pandemic similarly, using technology as an uplifting, yet removed touchpoint through video calls, coupled with time spent outdoors and socially distanced, safe interaction. Still, the longing for in-person reunion remained. As I sat shoulder to shoulder with my family, I couldn’t help but feel the overdue joy in the moment of finally connecting, intentional in our time. The autograph book went home with me that night, a piece of history, now displayed on my bookshelf as a reminder to value those that surround me and take the time to tell them through written word how much they mean to me, similar to my favorite salutation from my grandmother’s friend, Rosemary.

Yours till the Sunday Evening Star climbs the Saturday Evening Post.

Natalie Bickel is an energetic storyteller and PR specialist who aims to move people to action with her words. She has a bachelor’s in communications with published articles in Glamour, Darling Magazine, The Celebrity Café, and The Louisville Cardinal and features in Stylist, Shondaland, Refinery29, Woman’s Day, and more. Through her journalism experience, she’s interviewed celebrities, worked with musical artists, and reported on current trends and events. When she’s not writing, you can find her taking film photos of her dog, pressing flowers, or blazing new trails with her husband.