She is a somewhat polarizing figure, but author, journalist, and outspoken Muslim feminist Mona Eltahawy is responsible for sparking some very important conversations about the representation of women in Arab culture, and how the West perceives them.

Mona was born in Egypt, moved to the UK with her parents (both doctors) when she was 7, and then moved on to Saudi Arabia as a teenager. Her award-winning journalistic career took her back to Egypt in 2011 at the prime of the Arab Spring when protesters gathered in Tahrir square to demand then-President Hosnki Mubarak to step down, which he eventually did. While it was a celebration for the country as a whole, it was short lived because of the change in power and the ongoing struggle to reconstruct an infrastructure that serves all Egyptians equally.

She was physically and sexually assaulted by riot police in Egypt, and subsequently detained for 12 hours by the Interior Ministry and Military Intelligence. Mona is not the only outspoken journalist to share a horrific assault story while covering the uprising. American 60 minutes correspondent Lara Logan was on the ground in Tahrir Square when she was violently pulled away from the safety of her camera crew and bodyguards by male protesters, and sexually assaulted. She told her gut-wrenching story on 60 minutes where she talks about thinking she was going to die in that moment.

Stories like Lara and Mona’s are shocking, especially given that they are journalists. But what should also be just as shocking is that this culture is widely reported to be happening amongst Egyptian women every day. It is reported that 99% of Egyptian women have either been harassed, touched inappropriately or physically assaulted. And it took up until 2014 for the country to finally criminalize sexual harassment. Wow…

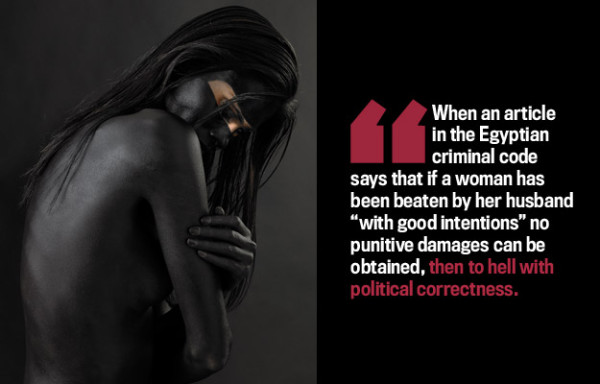

In 2012 after her ordeal, Mona wrote an essay for Foreign Policy titled ‘Why Do They Hate Us?’ (featuring controversial images of naked women with a black Niqab painted on them) where she goes to great lengths outlining the war on women in the Middle East. Her call for a revolution in the Arab culture centers around the treatment of women and sexuality. This is what has made her somewhat of a controversial figure among many different groups around the world.

Blogger Larry Hart penned a scathing open letter to Mona about the way she spoke of Americans, as did Shirin Barghi at Souciant, but there are other writers, commentators and bloggers who have taken issue with her perception of the treatment of women according to what she has seen and experienced. Is this a bad thing? Hell no! In fact it means her article was the catalyst that has sparked many more open conversations about this complex cultural situation that is often showcased in a very skewed, narrow-minded way in the media.

We applaud Mona and many other men and women who are seeking to bring the conversations about the unequal treatment of women by the hands of men in the Arab world to the forefront of social discourse.

She has released a new book called ‘Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs A Sexual Revolution‘ (which we cannot wait to read) and told the Guardian why it was important for her to write about rape, female genital mutilation and how she found feminism as a teenager.

Moving to Saudi Arabia as a teen girl, a time in life which is already fraught with so many tensions and insecurities, was the catalyst in opening her eyes to the need for feminism.

“In the UK, my mother had been the breadwinner. I’d seen my parents side by side. In Saudi Arabia, my mother was basically rendered disabled. She was unable to drive, dependent on my dad for everything. The religious zealotry was so suffocating. And I had been raised a Muslim, I came from a Muslim family, but this was ultra-zealous. As a woman in Saudi Arabia, you have one of two options. You either lose your mind – which at first happened to me because I fell into a deep depression – or you become a feminist,” she said.

Mona has copped a LOT of flack for her views but it hasn’t deterred her from bringing up some very important points, in light of what she and other Egyptians went through in 2011. She calls for more than just a political revolution.

“What happened in Tunisia in 2010 was a political revolution driven by recognition that the state was oppressing everybody. But I think when women looked around afterwards, they recognized that the state, the street and the home still oppressed women specifically and that trifecta of oppression means that political revolution, unless accompanied by a social and sexual revolution, will fail.”

In a video interview with the Guardian not long after her attack in 2012, Mona explains the cycle that perpetuates this discrimination toward women, saying when the regime don’t prosecute attacks on women, the attacks feel they can get away with it, and it sends a message to everyday men and boys that women’s bodies and lives are fair game.

In that same interview she lists many other female journalists who were attacked like her, including Lara Logan, saying that it was a direct attack on the voice of women who are speaking about important issues to the rest of the world through a specific female lens. During her attack she too thought she was going to die, but managed to push through it.

“There was one point when they took me to this no-man’s land where they sexually assaulted me and I fell to the ground and this [internal] voice said to me: ‘If you don’t get up now, you will die’. I managed to get up with two broken arms and fight them off. I was literally taking hands out of my trousers,” she said.

Coming from a woman who has not only experienced sexual violence, but saw it happen to her fellow country-women every day in Egypt, it sends a powerful message to gender violence victims that speaking up is important.

She told Vice News in an interview in March 2014, the revolution needs to happen in the home as well as on the streets. Despite getting flack for her 2012 article, she is not backing down because although she had many women write to her who say “my dad doesn’t do that to me” or “my brother doesn’t treat women that way” her point was about what happens to women when they leave the home and walk down the street. Those attitudes by men are learned in the home, however, and need to be revolutionized just as much as the political structure of the country.

“I was on an Al Jazeera show called Head to Head and discussed that essay. I was challenged at great lengths by the audience and the host and I think it served as a title change for me. It’s not something I say just to be controversial. It’s something that I say because I’m Egyptian and I’m a woman. So, as painful as it was for some people to read that article, I think [we need to be] honest about this kind of patriarchy and take this revolution into the home. Just as we overthrew the Mubarak in the streets we have to over throw the Mubarak in the home,” she said.

Her upbringing gave her a vastly different perspective on equality between a man and a woman than many other traditional families in the Middle East, which is why the social cues she learned in her home, she is taking to the streets and speaking about it publicly.

“One of the wonderful things about the home I grew up in is that my parents met at medical school: they got their masters together and their PhDs together. So from a very early age, I saw a relationship of equals functioning together that gave my brother and then my much younger sister this great template for us to work to. It showed us that you can grow up in the home as equals and that boys and girls and men and women can have access to all the education that they want.”

Although Mona is based out of New York these days and became a US citizen in 2011, Egypt is a huge part of her heart yet sees many parallels between the struggles of feminists in both countries

“When I tell my American friends about what we’re fighting for in Egypt, I’ll remind them to ask their grandmothers to see what it was like in the US in the 1940s. In some places today in the US, you have the right wing trying to roll back reproductive rights and only teach abstinence. There are places in America where there is no sex education given to kids. The connections that I make are where the religious right wing is obsessed with having a foothold and they’re obsessed with my vagina.”

She mentions sex education being largely absent from Egyptian schools and society, but having doctors as parents, she was lucky enough to be armed with the right information from a young age.

“Sex is not something that’s taught in Egypt and teachers are embarrassed to talk about it. It’s something you read about at home. In some instances, parents will pull their daughters out of these classes. They don’t want them to be involved in anything that’s sexually educational. When a girls reaches her wedding night [when they’re expected to be a virgin] some kind relative may just have to explain to her what is going on. There’s a huge black hole.”

The truth is we need more men and women like Mona who are willing to stand on the front lines of this war against women in Arab cultures and across the Middle East and bring light to important issues. Sure, she may stir up anger, and conflicting opinions, but the issues surrounding Arab women are becoming more and more common thanks to journalists like Mona who aren’t afraid of a little controversy in the hope that women around the world are afforded a much-needed public voice they never had before.

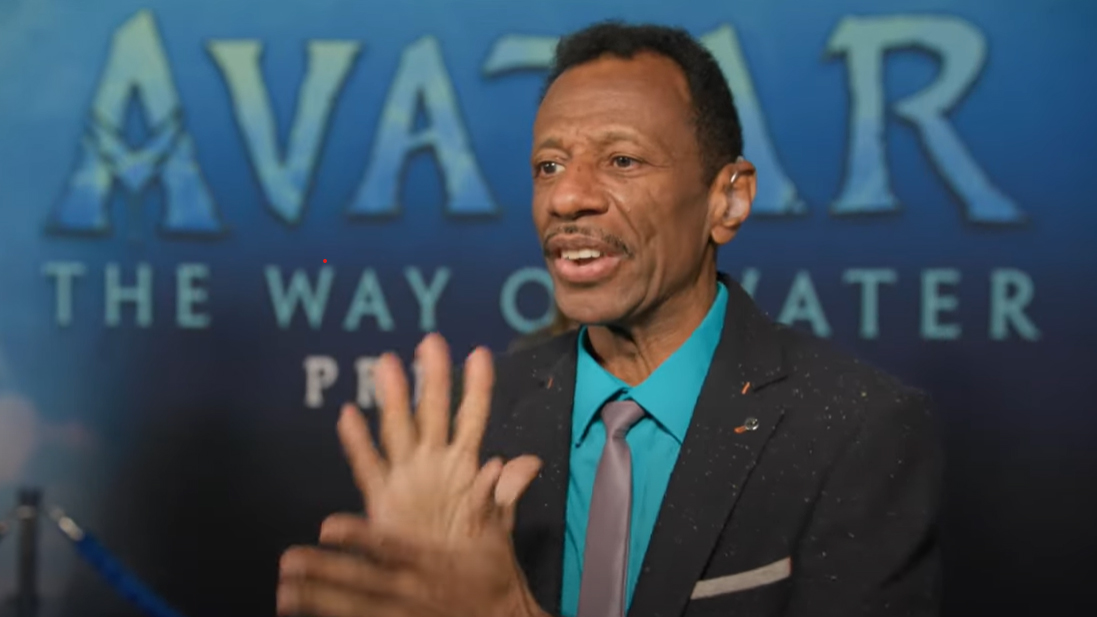

Take a look at her on the Melissa Harris-Perry show in 2012 talking about her Foreign Policy article and why she is adamant that the Muslim world needs a sexual revolution as much as a political one:

7 thoughts on “Feminist Author & Journalist Mona Eltahawy Says The Middle East Needs A Sexual Revolution”