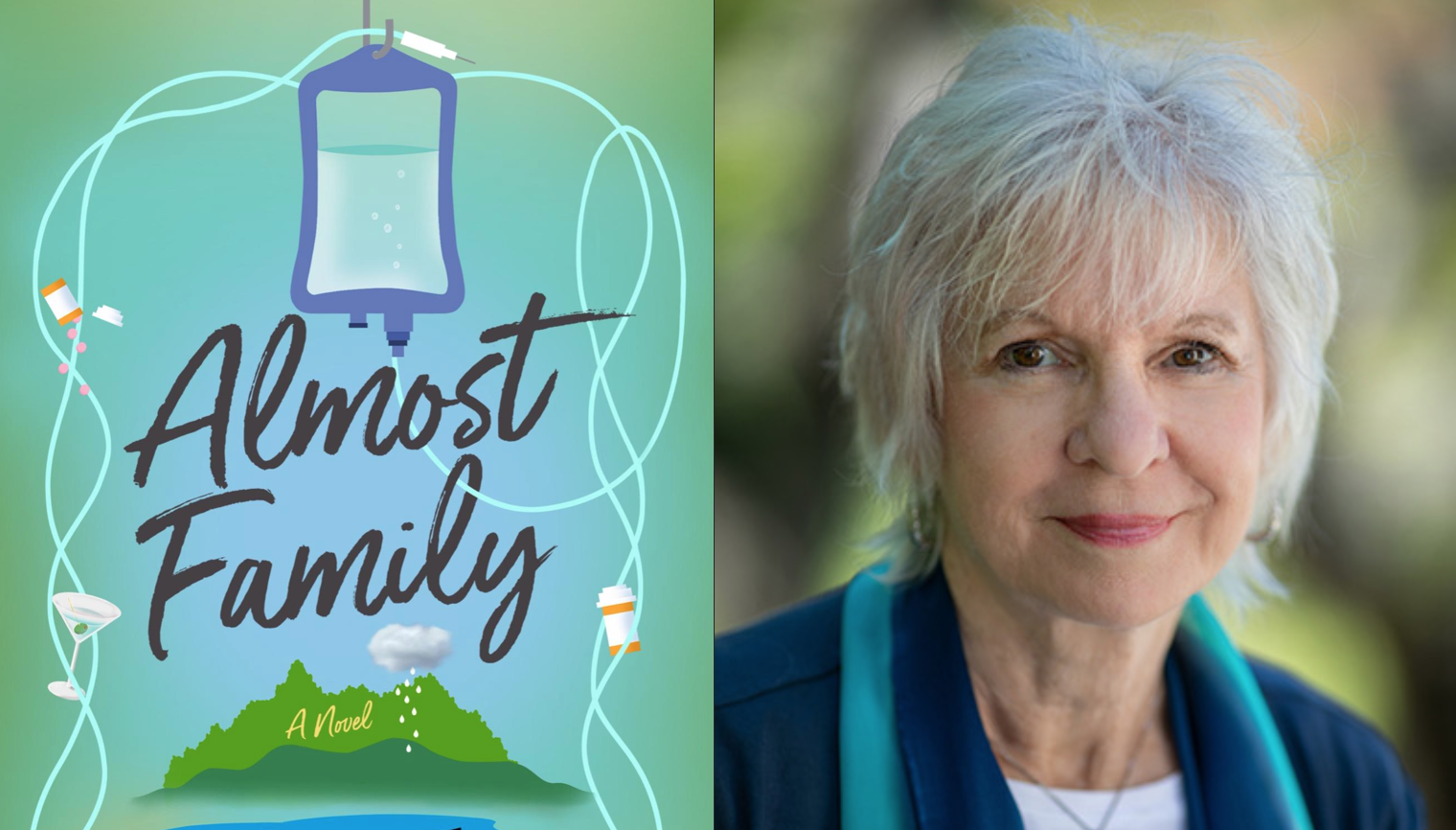

The following is an excerpt from author, award-winning journalist and psychologist Jean K. Carney’s ‘Blackbird Blues’ (October 1, Bedazzled Ink Publishing). Following the death of her teacher and mentor Sister Michaeline, aspiring jazz singer Mary Kaye meets Lucius, Sister’s former love and father of their estranged son, Benny. The two unite to bond over their mutual loss, with Mary Kaye helping Lucius and Benny mend their fractured relationship. Decades of secrets lie behind the heartache as Mary Kaye struggles with an unwanted pregnancy that could derail her dreams.

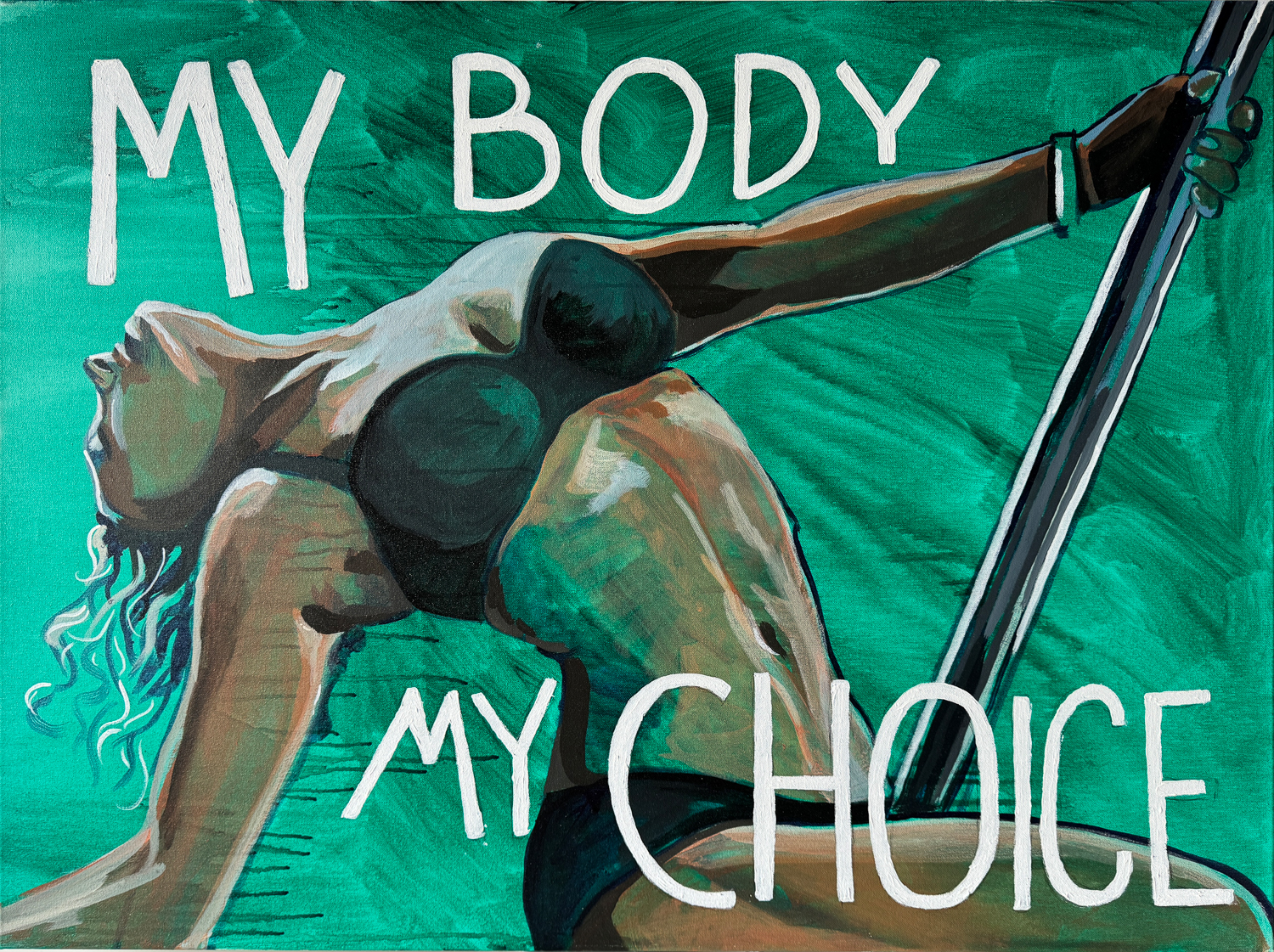

Carney’s work as a reporter covering Roe v. Wade, her extensive research, and decades of experience as a psychologist helped her write this stunning piece of fiction with historically accurate characters so realistic it’s as if they were pulled right off the streets of Chicago during the Civil Rights era. Behind its themes of racism, abortion, and child abandonment, this heartbreaking and timely novel ponders two pressing issues of human existence: What do we owe our children? What do we owe ourselves?

Around the bend, ahead on the expressway, toward the city center, red taillights snaked as far as she could see. The road looked as slick as a mirror. Next to her, on the side of the car, rain pelted and pierced a puddle. How could something look so dazzling, so mesmerizingly smooth when it was far down the road, and look so blown to smithereens up close?

They sat on the Edens, waiting for the traffic jam to unwind.

She said fervently, “No matter what happens with the rabbit test, I don’t want to get married.”

“Give me a chance. We haven’t even talked.” He put the gear in park and revved the engine.

“We’ve got no business getting married, and you know it. We’re nowhere near old enough.” She stuck her arm out the window and slapped her hand on the roof of the car. “There’s nothing to talk about. I’m not getting married.”

“You may change your tune when you actually hear what the rabbit test said.”

She was not going to cry. Frantically, she tried to calculate in her head. It would be nine months from April 7th. Or did you start counting from your last period? She switched the radio off.

“I bet I’m pregnant. How long have you known? I thought you’d tell me right off tonight if you had results.”

An ambulance roared up the shoulder of the road alongside them, siren wailing. No wonder traffic wasn’t moving. A car had crashed not far away, on the other side of the median, going the other direction. In her mind’s eye, she could see the ambulance, its back doors wide open. She could see inside. Somebody was lying on a stretcher. She could not help but wonder about that person. She couldn’t see him or her and she might not ever know the identity of that person, but he or she, or maybe it was they, had become a part of her life, and at the moment, they were holding up her life. She wanted them out of the way. She felt that clearly. She was numb, but her thoughts were not in a jumble. It was a little cooler after the rain, but the vent kept bringing in exhaust and soot. The air did not feel clean. Traffic began to inch forward.

“Let’s go someplace and talk.”

“I don’t want to go someplace. I want to go to the Jazz Emporium.” Sister had trusted Lucius enough to give him her book, and she was going to put her faith in him too. She had a big problem but she did not need to be alone with it.

“How did I get roped into driving in a colored neighborhood? Trying to please you again. I could care less about jazz music.”

“Well, then why don’t you drop me off and drive home! I don’t need you to hold my hand and complain about the music. I can get back on my own.”

“You think I’m going to leave you alone in this jungle? You gotta be kidding.”

“I’m not kidding. I’ve had it with the snide remarks and the Mr. Big Man performance.”

“Watch your mouth, little lady. You’re pushing your luck.”

She could not stand the sight of him. How could she have gotten mixed up with a guy who had scored a C in algebra, flunked second grade, barely finished high school? Whose father was connected with shady people? For God’s sake, at the age of nineteen, Tony even had his own bookie.

They drove in silence for a long time, until she could stand it no longer. “Tony, you’re not watching the signs! You’ve got to get off at 47th Street.”

He cut across two lanes of traffic, nearly got rear-ended by a moving van and skidded on to the exit ramp. “You say you don’t want to get married. So what’s going to happen? I’ll be goddamned if I’m going to stand by and let a stranger raise my child.”

“It’s not about you. I’m the one who’s going to have a baby. We’re not talking about what you’re going to do. We’re talking about what I’m going to do.”

“I’m trying to talk sense and you’re stuck in la-la-land. Typical girl. Doesn’t give a damn about me. It’s my baby too, you know.”

She bit her tongue.

He turned the radio on again. Dick Biondi took them through “Walk Like a Man,” “My Boyfriend’s Back,” and “Can’t Get Used to Losing You.”

They drove down 47th Street, Mary Kaye reading the street numbers aloud.

“Slow down,” she said. “You’re going to pass it.”

“You know what?” he exploded. “I don’t need this bullshit. Have it your way. You keep treating me like I’m an idiot. I’m not going with you. I’m not going to listen to that god-awful music. I’m going to drop you off and then I’m driving home. See how you like going in there all by yourself.”

“Watch me.” He had rattled her, but she was not going to back down.

When they pulled up to the club, she got out of the car and slammed the door in the middle of Andy Williams. She could hear that Tony had not pulled away from the curb, but she kept walking. She followed a group of couples to the vestibule. A young black man dressed to the nines held the door for her and she followed his date into the darkness.

So this was the Jazz Emporium. She was too furious and too shaken up to look for the place under the photo of Billie Holiday, alongside the Steinway. She grabbed a chair at the end of a row of tables and swiveled to check out the crowd. Blacks, whites, and mixed couples bowed over cocktails, reading newspaper reviews of Chicago jazz greats laminated on the tiny tabletops.

Early arrivals had nabbed raggedy brown leather loveseats along the walls, under photos of Armstrong, Goodman, Krupa, and Hines—familiar faces from Sister Michaeline’s class. Some perched on the sassy hot pink leather and rattan stools around the mahogany horseshoe bar in the back. She wondered how many others had got in with phony IDs. The white pianist intoned the first bars of “It Could Happen to You.”

JEAN K. CARNEY is the author of “Blackbird Blues” (Oct. 1, 2019, Bedazzled Ink Publishing). She spent eight years as an award-winning reporter and editorial writer at the Milwaukee Journal, covering Children’s Court, City Hall, and Roe v. Wade. She earned a Ph.D. in Human Development at the University of Chicago and trained at a large Chicago inner-city psychiatric hospital. She taught psychology at St. Xavier University. In full-time private practice as a psychologist for 30 years in the Chicago Loop, she saw patients from all walks of life and ethnic backgrounds in psychoanalytic psychotherapy. After her husband died of ALS, she edited his last book, “Jewish Writing and the Deep Places of the Imagination,” stopped publishing in professional psychoanalytic venues, and turned to fiction.