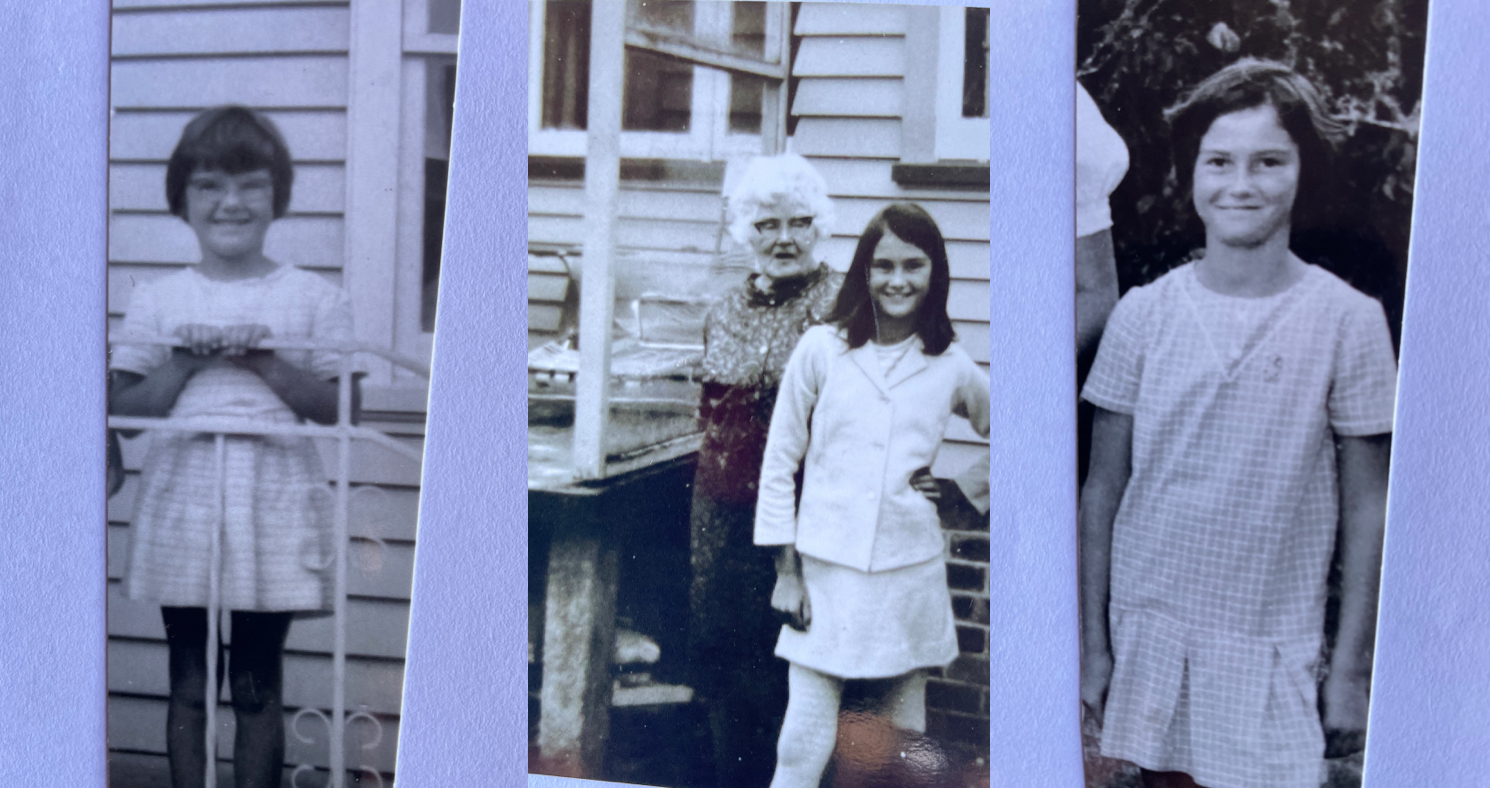

By Susanne Dunlap

My pronouns are she/her/hers. I’ve always been comfortable with my birth gender, in spite of having come of age in the sixties and seventies when feminism was in its infancy, if a concept at all. In my lives as an advertising copywriter, a nonprofit executive, a music history professor, and other occupations, I experienced overt and covert misogyny firsthand, but I never wished to be anything but a straight female.

And yet, clearly something was at work through all those years, something that made me decide to take a feminist lens to music history in graduate school and foreground women artists in my fiction. A young female Viennese violinist is the amateur sleuth in my YA historical mysteries. All my published adult historical novels heavily feature the art of the female protagonist, whether it’s visual arts, music, acting, or film-making. This is nowhere more apparent than in my twelfth historical novel, ‘The Portraitist’, which comes out on August 30 and is the story of a real-life woman artist of the eighteenth century.

It’s true that the arts are only one realm where women have been given short shrift over the centuries, and they’re arguably the least important. Nonetheless, it’s where I’ve chosen to focus my energies as an author. Why?

The origins

Perhaps it all started with wanting to be Mozart. As a child, I showed natural talent for music very early on. That was doubtless the reason someone—I have no recollection who—gave me the storybook called ‘Mozart the Wonder Boy’, by Opal Wheeler and Mary Greenwalt. I became obsessed with the remarkable prodigy who performed for royalty, sat on the laps of empresses, and dazzled all the adults with his astounding talent.

What I don’t remember registering at the time was that Mozart had a sister, Nannerl. Their ambitious father dragged the two of them from place to place, looking to make a fortune. Wolfgang was younger and therefore cuter and more remarkable. But by all accounts, Nannerl was just as talented. Why didn’t I want to be Nannerl? I can only guess at this distance of many decades, but I suspect it was because I wanted to be the star, not the understudy, and in that book Wolfgang was absolutely the star. There’s no question that the name Mozart refers to him, not his sister.

I was too young to understand that forces beyond Nannerl’s direct control prevented her from fulfilling her own destiny as an artist, and possibly becoming every bit as famous as her brother. She played the violin better than her brother did, but the violin wasn’t a suitable instrument for a lady because of its association with the devil and sin. She composed music, but that wasn’t a proper role for women either at that time. And when she reached marriageable age (around fifteen), all touring and performing stopped for her. She was told to (and did) focus on her true role as a potential wife and mother.

The only evidence we have of her creative endeavors is a reference in one of Wolfgang’s letters to her that he liked the minuet she composed, which she had sent to him.

A sad refrain

Nannerl is just one example of a woman artist who was not permitted to fulfill her potential because of obstacles that included family expectations and responsibility, access to training, societal norms, feelings of inadequacy, time, conflicting demands, and so on. The same forces that for centuries prevented women in western culture from stepping into roles as doctors, lawyers, politicians—you name it.

But this still doesn’t answer the question of why I am so obsessed with women as artists, why their stories are the ones I want to elevate rather than the arguably more dramatic and important women who became fighter pilots, or who discovered something world-altering, or forged a way into the male-dominated hard sciences.

I do it not just because I’m interested, not just because I am a musician and a writer. I do it because I fundamentally believe the arts are vital. The arts we value reveal the truths of society, reflect what people care about, how they spend their leisure time, what they consider beautiful. Making art is a deeply important occupation, and for that reason, women had to struggle through the centuries to be acknowledged as artists on par with men.

My books are my own tiny attempt to drag these women of the past out of obscurity and bring their lives, loves, passions, disappointments, and triumphs to life for modern readers. The women artists of today, who have equal access to training and opportunities, stand on the shoulders of all the women who went before them. As do I, who owe a debt to the Currer Bells and Daniel Sterns who hid behind masculine pseudonyms to get their stories into the world.

No more hiding. I don’t have to be Mozart, because I can be Susanne, owning my work with all its imperfections as it sits on the shelf mixed in with novels by people of all genders. Is everything all perfect and rosy? Of course not. But of all the obstacles I face in getting my work into readers’ hands, being female isn’t one of them. And that’s a big change from the past.

Susanne Dunlap is the author of twelve works of historical fiction for adults and teens, as well as an Author Accelerator Certified Book Coach. Her love of historical fiction arose partly from her studies in music history at Yale University (PhD, 1999), partly from her lifelong interest in women in the arts as a pianist and non-profit performing arts executive. Her novel ‘The Paris Affair’ won first place in its category in the CIBA Dante Rossetti awards for Young Adult Fiction. ‘The Musician’s Daughter’ was a Junior Library Guild Selection and a Bank Street Children’s Book of the Year, and was nominated for the Utah Book Award and the Missouri Gateway Reader’s Prize. ‘In the Shadow of the Lamp’ was an Eliot Rosewater Indiana High School Book Award nominee. Susanne earned her BA and an MA (musicology) from Smith College, and lives in Biddeford, ME, with her little dog Betty. You can find her at https://susanne-dunlap.com