A new Middle Grade novel, ‘Morning Sun in Wuhan’ (out November 8, Clarion Books) from author Ying Chang Compestine offers readers a different perspective on the global pandemic brought on by COVID-19. The book captures the uncertainty and community-bonding and draws on the author’s own experiences growing up in Wuhan to illustrate that the darkest times can bring out the best in people, friendship can give one courage in frightening times, and most importantly, young people can make an impact on the world.

Ying is an award-winning author, speaker, and television host. She has authored twenty-five books for adults and children, including the acclaimed novel ‘Revolution Is Not a Dinner Party’, which chronicles her experience of growing up in China during the Chinese Cultural Revolution.

Weaving in the tastes and sounds of the historic city, Wuhan’s comforting and distinctive cuisine comes to life as the reader follows 13-year-old Mei who, through her love for cooking, makes a difference in her community.

Grieving the death of her mother and an outcast at school, thirteen-year-old Mei finds solace in cooking and computer games. When her friend’s grandmother falls ill, Mei seeks out her father, a doctor, for help, and discovers the hospital is overcrowded. As the virus spreads, Mei finds herself alone in a locked-down city trying to find a way to help.

We are excited to publish an excerpt from ‘Morning Sun in Wuhan’ below, to give readers a glimpse of what to expect in the book.

Chapter One

山雨欲来风满楼

The raging wind precedes the coming storm

January 19, 2020, Evening

It feels as though hours have passed since the waitress took my order. As I scroll through photos on my phone, part of me still expects a text from Mother to pop up.

Mother:

Where are you, Mei?

Finish your homework before

playing computer games.

Meet me at Double Happy for dinner?

How can the world exist without her? My eyes dampen when I come across a selfie of us. We were making rice cakes that day, and I patted flour on her face until she looked like a geisha. We

laughed until my stomach ached.

The woman at the next table puts another garlic shrimp into her daughter’s bowl. Mother wouldn’t have done that. She would’ve peeled the shrimp before giving it to me. Now that I think about it, she would have never ordered a shrimp dish with

the shells still on.

The girl doesn’t look up from her phone; she keeps pounding her thumbs on the screen, probably playing a silly, mindless game that doesn’t require skill or strategy. The woman catches me staring and smiles at me. I blush and avert my gaze to the window, looking past the four large red lanterns swaying in the wind. They cast a blanket of ruby light over the restaurant’s entrance.

Thunder rolls in the distance. Dark clouds are gathering over the hospital compound where Father works. From across the street, it looks like a big factory. Patients are lined up along its thick brick walls — more than usual, it seems.

Finally, the waitress with red lipstick appears, holding a round tray over her shoulder. She must be new, as I have never seen her before. I ordered Mother’s favorite dishes: lion’s head meatballs, stir-fried spicy lotus root, and steamed Wuchang fish— a sample of Double Happy’s signature dishes. The waitress’s head dips as she sets the dishes down, exposing the white roots of her hair.

“Need anything else?” she asks.

“No, thank you.” I use my confident voice and avoid her questioning gaze.

She stumbles away, no doubt wondering why a thirteen-year-old girl ordered so much food, only to eat alone.

The familiar smell of chili peppers in the lotus root and pungent black bean sauce over steamed fish brings back so many memories. The days when Father worked night shifts, Mother and I would meet here for dinner. She would come directly from work, still with indentations on her cheeks from her surgical mask. When I teased her, saying she looked like a Wuchang fish, she would suck her cheeks in and flap her lips. Grunting like a monkey, I would puff my cheeks and pull my ears. Our laughter always drew attention from the people around us.

“Eat a bit more,” the woman urges her daughter. The girl doesn’t respond, eyes still glued to her phone.

How many times did I act like that when I was here with Mother? If only I could have one more meal with her, I would never ignore her again. Like a song on loop, I can’t stop replaying that dreadful day in my mind. I was so happy when I first received the text from Mother.

Mother:

I’m running late and canceled your piano lesson.

I smiled, glad I had more time to improve my ranking on my video game, Chop Chop Chef. In the midst of cooking for my soldiers, who were furiously fighting zombies, Father burst into the apartment sobbing. I didn’t — couldn’t — understand what he said that day, and even after a year, I still can’t comprehend it.

I put a few slices of lotus root in my mouth. The chili burns my tongue. I quickly take a bite of the meatball. Its mild taste neutralizes the sting. Did Chef Ma cook these? With the tips of my chopsticks, I pick up a piece of the fish’s belly; Mother always served it to me, saying it was the most tender part of the fish. With every bite, I hear her voice.

“Chef Ma makes the best meatballs. Eat more of the lotus root; it’s good for your skin. Taste the fish; it’s from the Yangtze River. We are lucky to live in Wuhan.”

It’s been a while since I feasted like this. By the time I’ve made a big dent in all the dishes, the restaurant is packed. Finally, I get my waitress’s attention and ask her to pack my leftovers.

Father will probably work late again tomorrow. The leftovers will be a nice dinner for me. During the rare times I do see him, he is always staring at his phone. Will he work late every night? Maybe I should have gone to live with Aunty.

Even though I don’t blame Father for Mother’s death — like Aunty does — I can’t help but wonder if Mother would still be here if he hadn’t always been busy at work, leaving her to runaround and do everything.

More families trickle into the restaurant, and raucous parties fill up the two big, round tables in the middle. We used to meet

Aunty here, but I haven’t seen her since I refused to live with her after Mother’s death. Aunty has been upset with Father ever since he discouraged Mother from quitting her job at the hospital to work in Aunty’s private pharmacy.

The memory of Aunty screaming at Father after Mother’s funeral is still so vivid.

“She should have never married you!”

My thoughts are interrupted by retching coughs. It’s my waitress, now standing in the middle of the aisle, a few tables down from me. One hand holds my take-out boxes while the other stifles her coughs, smearing her lipstick into a red mustache. She stumbles a few steps forward, then breaks into another violent coughing fit. The bustling restaurant falls silent and everyone’s eyes fixate on her.

Suddenly, she collapses facedown on the floor, motionless. The boxes slip from her hands and break open. A few meatballs rollunder the tables, and the dark sauce stains the red carpet. The restaurant erupts like a geyser; people spring from their seats, chairs jostle, and utensils clatter to the ground. Panicked voices slice through the air.

“Doctor! We need a doctor!”

“She could have the new virus!”

“What’s that?”

“It’s deadly. It’s contagious!”

Everyone swarms to the front door. I grab my bag and slip out the back.

Cold rain drizzles down and quivers under the streetlights. I shiver and pull up my hood, running past the growing line of patients outside the hospital. A thousand questions race through my mind as I hurry home. What just happened in there? Will someone take the woman to the hospital? Is she dead? What “new virus” were they talking about?

Surely, Father has to know; he is the director of the respiratory care department. Then again, is he even home?

When I open the door, I hear the sound of a drawer closing in Father’s office.

“Hello, Mei.” Father rushes out into the living room.

“You’re home!” I exclaim.

He glances at his watch. “I’m leaving in a minute.”

“What?” I kick off my shoes, slamming the door behind me.

“Where are you going this late?” I struggle to stay calm and throw myself on the sofa without taking off my damp coat.

Mother would have disapproved. She always insisted that I leave my coat in the entryway, but Father doesn’t seem to notice. He points to a pile of masks on the coffee table in front of the TV.

“From now on, wear a mask when you go out. For everyone’s safety, give one to each of your classmates and teachers.”

“Safety from what?”

“I can’t talk right now.” He dashes to the door and turns to look at me. “Sorry. I’ll explain later. Make sure to wear a mask! “He closes the door quietly behind him.

It’s flu season, but there is no way I am going to be the first to wear a mask and get teased at school. And what will my classmates think if I randomly hand out masks like a street peddler? Where is he going now? When I visit him in the hospital, I always notice the young nurses flirting with him. They blush and twitter like birds around him. Is he secretly dating one of them?

My eyes land on a photo on the TV stand. The frame is made of heavy green bamboo, as though to protect the memory inside. I reach out and pick it up. Mother captured the moment just before I threw the snowball — my first one to successfully hit Father. I could tell he was laughing even though our faces were silhouetted by the lit-up snow sculpture behind us.

At the beginning of our snowball fight, I made mine too big. I could barely throw them a few feet, and some even crumbled before leaving my hands. Father laughed and teasingly called them “wimpy shots.”

I was frustrated, but when I watched how he made them, I figured out my mistake. I took my time packing the powder into perfect, persimmon-size balls. On my third try, the snow held its shape until it smashed into Father’s forehead. He cried out, sank to his knees, and fell back.

Mother and I giggled as we ran over to help him up. His eyes were shut, and snow slid down his face, leaving snail-trails of freezing water on his skin. I stopped giggling when he remained motionless. Suddenly, his eyes flew open, and he dragged us down. We shrieked with laughter and rolled around in the snowlike three happy bears.

That night, we went to Harbin’s famous Ice Restaurant. We waddled inside like penguins in our heavy winter jackets, shivering until our waitress brought out the restaurant’s signature spicy beef noodle soup, steaming hot. We competed to see who could slurp noodles the loudest, and forgot we were eating on tables made of large ice blocks.

Since Mother’s death, Father has changed so much. I can’t even remember the last time he smiled. He used to play his erhu after work. I wonder if he will ever touch it again.

Sad and exhausted, I put the picture back onto the TV stand and drag myself to bed. I pull the covers tight over me, wishing I could choose my dreams. I would dream of our family’s last vacation in Harbin.

But instead, I dream of the coughing woman, holding a stack of take-out boxes, stumbling toward me.

You can order a copy of ‘Morning Sun in Wuhan’ by clicking HERE. This excerpt was published with permission from Clarion Books.

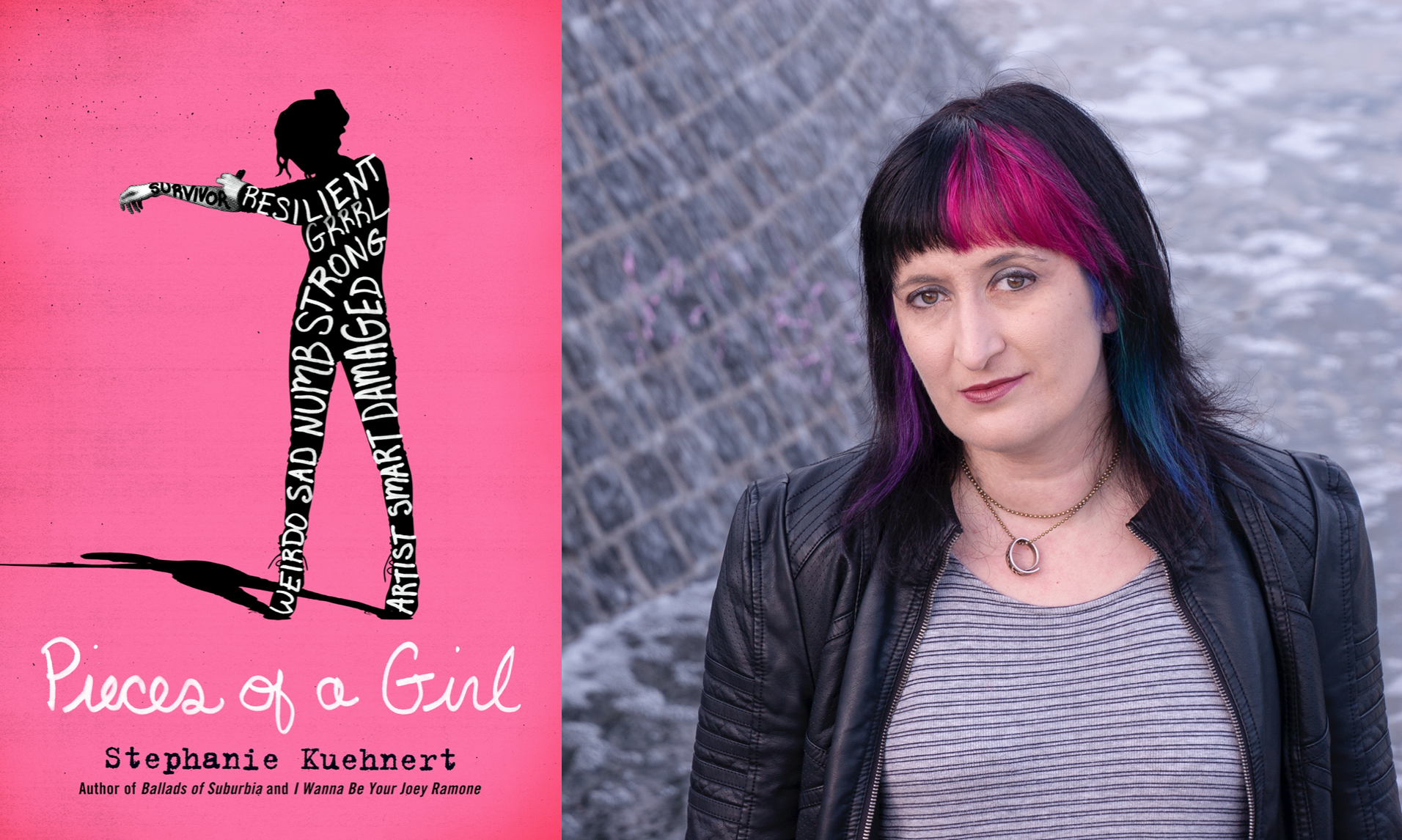

Author Ying Chang Compestine