Activist and poet Fatima-Ayan Malika Hirsi released her debut full-length poetry collection ‘Dreams For Earth’ in September, arriving at a crucial inflection point in our shared humanity. As we experience an increase in political unrest and a growing distrust in existing systems and institutions to act in our best interests, it is a timely reminder that art is not only a necessity in times like these, but a powerful act of resistance.

Many of us are experience a collective grief over what we are witnessing, and Fatima-Ayan not only shares this but puts to words what she has been experiencing and feeling in her new collection. ‘Dreams For Earth’, is a fierce and luminous work that lives at the intersection of race, climate grief, and political resistance and features illustrations by Ángel Faz & Jack (Anna) Jackson.

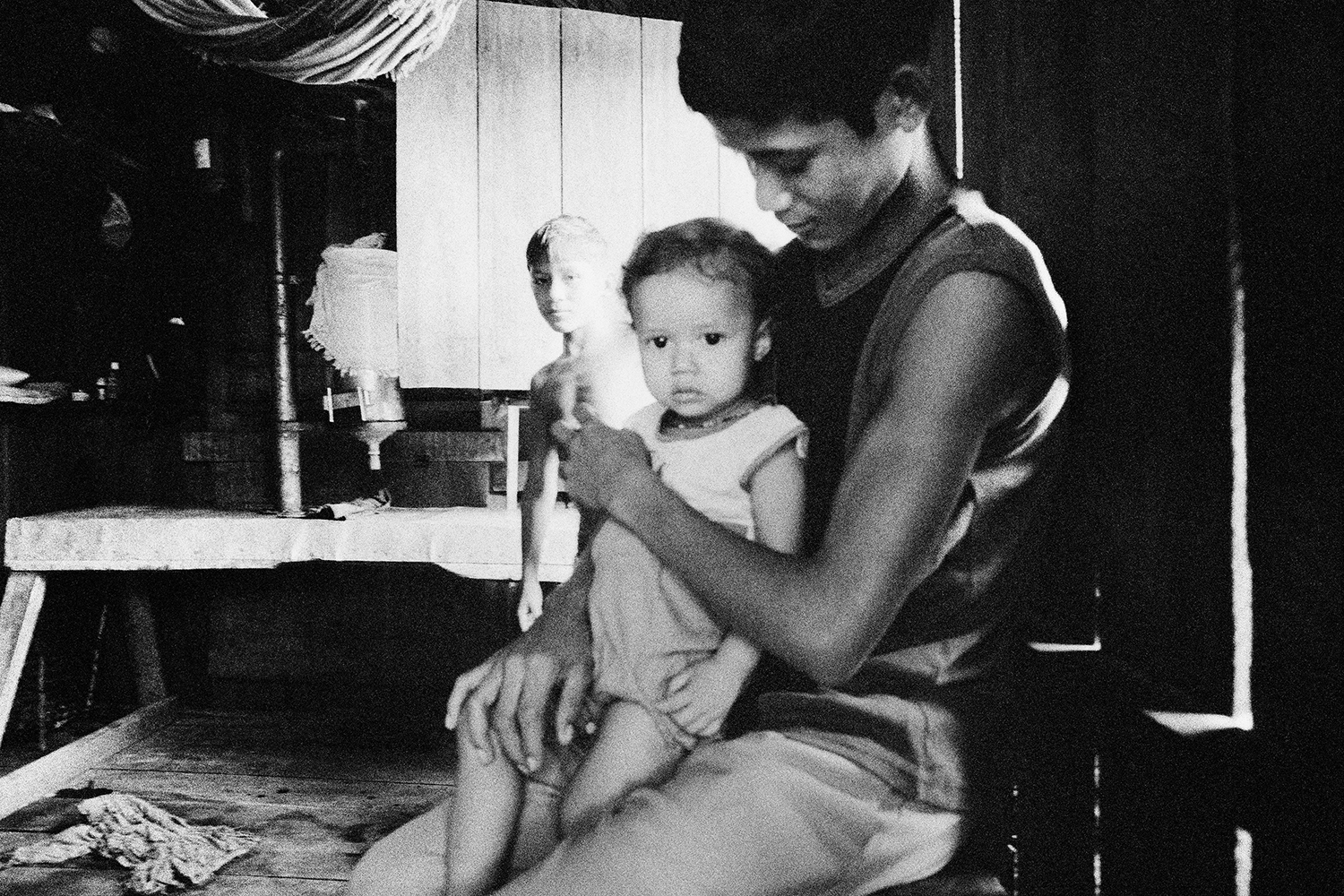

With ferocious joy and searing insight, Fatima-Ayan’s poems confront what it means to nurture a child in a world facing ecological collapse; bear unflinching witness to atrocities of police violence, zionist occupation, and shattered genealogies; and cherish the beauty of life and earth.

The collection delves into what it means to be a Black Mother in today’s America, where we see an increase in maternal mortality rates disproportionately impacting Black women due to systemic racism embedded into our healthcare system.

Fatima-Ayan interweaves political organizing into her art, where her pre-order campaign proceeds went toward Workshops4Gaza. Equal parts prayer and protest, the poems invite us to live fully in the power, responsibility, and joy of our interconnectedness.

In an interview about this debut full-length collection, the activist, poet and mother spoke with us about her perspective as a Black Mother raising a child in today’s world, how motherhood informs and shapes her political perspective in thinking about the mothers in Gaza, and how her poems had such a profound and emotional impact on her as she was writing them.

How did you prepare for the release of your debut poetry collection, and how do you feel now that it is out in the world?

I’m preparing by grounding into what makes me smile, like going to the ocean, planning the fall garden, and rejecting the expectations of capitalism that come with releasing a big creative project. Embracing slowness and leaning into invitations with others that involve writing over admin have been a welcome change. This book spanned five years of my life, so its release feels like a clearing of space within me. Working through the whole publication process meant constantly being in conversation with so many past versions of myself, and now I feel able to let go and be very present with who I am at this moment.

How long have you been working on DREAMS FOR EARTH, and how did the idea for the collection begin?

I signed my contract the spring just before Covid erupted and added the last poem in late 2024. I hoped to write a collection about my experience as a Black woman who loves the earth and dreams of different worlds, but I didn’t know what exactly that would entail. I wrote the book very similarly to how I write poems; I begin and have no idea how an ending looks until it arrives.

Your work touches on important topics that have become too potent to ignore in today’s climate. Let’s first talk about motherhood – what was the message on your heart that you wanted to share, knowing the fractured and fraught ways motherhood, especially Black Motherhood, is treated in America right now?

I want all people to really appreciate that bringing forth and nurturing life is a sacred work. It’s so much like gardening. In the present moment, you’re watering and fertilizing, but you’re also nourishing a being to grow into the future. It is a massive act of world-building, because how you go about your role as the gardener has such a large impact on how this being moves through the world.

I really wanted to highlight the intentionality of showing my children the Earth’s softness alongside other realities we’re forced to confront. Tiny hands touch dandelions with wonder / We sing songs to the sky against the police loud enough to wake thunder. I think most parents want to raise kind children, but a piece too often missing is teaching our children about experiences outside of their own.

James Baldwin said, “The children are always ours, every single one of them, all over the globe; and I am beginning to suspect that whoever is incapable of recognizing this may be incapable of morality.” Being a Black woman raised in the South, I have seen how people come together to take care of each other and each other’s children.

Conversely, I have also witnessed up close ways empire tries to make it challenging to offer care. I’m thinking now about how acts like leaving water out for migrants or offering water at polling stations in blistering Texas heat can have legal consequences. So caring for others can sometimes require gorgeous and courageous acts of creativity that shouldn’t be necessary.

The law is not concerned with what’s right. I can’t think about being a Black mother in the United States without thinking about what it’s like to be a mother in Gaza. I yearned for motherhood in a state with the highest Black maternal mortality rate in the country. It’s no mystery why, and it’s connected to why mothers in Gaza right now can’t feed the children who survive the bombs. White supremacy touches every facet of life. We are all connected in a collective kinship, and that’s what I hope comes across in my book.

You mention the notion of climate grief. Can you explain more about this, and why what we see happening to the environment is a cause for mourning and grief right now?

I have positive memories of growing up and feeling a sense of intimacy with the weather. Seasons contained predictable patterns. I think what’s happening to the environment is cause for grief and mourning, and rage, because those experiencing the bulk of climate catastrophes aren’t responsible for creating them. Two years ago Oxfam produced a report explaining that the richest 1% are responsible for as much planet-heating pollution as 66% of humanity.

The Guardian says 100 companies are responsible for 71% of global emissions. I didn’t grow up with a world that had snow in the Sahara Desert and fires in Alaska. We’re giving future generations an unrecognizable world because those in power prioritize the profits of corporations over their impact on people. While the Environmental Protection Agency rolls back regulations and erases reports, they’re also erasing a future in which my daughter knows the wonder of witnessing fireflies light up the evening.

There are now dangerous levels of forever chemicals in ocean spray, but I still walk into the ocean because it’s one of the ways i pray. When my daughters are teenagers, will they still be able to swim in the ocean—how will climate catastrophe not only affect our physical selves, but the spiritual selves of those connected to land? Corporate interests try to cut the cord of people connected to the land in a thousand ways.

We are seeing that right now with climate activists facing terrorism charges, with fragile wetland and forests being removed for Alligator Alcatraz and Cop City. We’re seeing it with the demolition of agricultural land in Gaza and the uprooting of olive trees hundreds of years old. The emissions of the war machine have an egregious effect on the climate worldwide, so every reason we have to grieve is connected to another reason. No joy and no mourning is in isolation.

Can you talk about the intersection of racism and climate change, and how you interwove these aspects into your collection?

Audre Lorde said, “There is no such thing as a sing-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” I’m thinking about the birth poem for my oldest daughter. It was fire season in Oregon and we lived in a barn with no ventilation. Every fire season we’d leave home amongst the trees to be at the coast where air was clean. I had a lot of fear about going into labor away from my midwife because I had a home birth planned.

In 2016 half of the 222 medical students surveyed thought Black people felt less physical pain than white people. I was afraid that if I had an unplanned hospital birth on the coast supported by people unfamiliar to my humanity, that it would result in unwanted interventions. I’m also thinking about my mother’s garden in South Dallas, and how my family’s neighborhood is located directly alongside a cement plant that spews ash across the historically Black neighborhood formed in the 1860s.

My mother stopped gardening in Joppa because she didn’t feel she could eat the vegetables covered in a layer of grime. Some days I’d open the front door and be slammed by a stench that made me hold my breath on the way to the car. This is a micro example of what happens on a macro scale. There are no industrial plants releasing toxic ash in Highland Park, one of the most affluent parts of Dallas.

What were the hardest topics to write about, and what brought you the most inspiration, when putting together DREAMS FOR EARTH?

When I say hard to write, I don’t mean writer’s block or the idea of running away or not being ready to confront a topic, I’m talking about possession. I’m a quadruple Scorpio and feel everything with exponents. A haunting is all-encompassing. There are poems in the book that took me away from my family. They unfolded inside me over the span of weeks, or longer, and affected my emotional presence with those I love.

Me and my husband ended up in marriage counseling, because it was hard witnessing me witness. It doesn’t feel right to talk about challenges related to metabolizing being witness to a genocide in my phone, or the rage of being gaslit that it isn’t happening—my experience is nothing beside those living through what the world continues to this day to only watch, or worse, enable. I want us to individually and collectively move beyond witnessing toward a place of action.

The most inspiration came from my time beside the ocean, or in the forest, and seeing ways the Earth has no boundaries or borders on care. I want that for us as people. One of my favorite books is ‘Love and Rage’ by Lama Rod Owens, because it so beautifully ties together two feelings that dominant society does not place beside each other. It shows how the root of some of my (and others’) rage is love. We love each other so fiercely that we are consumed by rage at those who would deny joy, or food, or limbs, or parents to a person because of where they are born or what they look like.

Despite so many atrocities, you also focus on the joy and beauty of life and earth. Why was it important for you to give readers permission to think about joy?

If we aren’t present with what gives us joy, how can we address forces that would steal it?

The illustrations in the collection are stunning and so thought-provoking. Can you tell us about working with the artists, and what their images mean to you personally?

I wanted to be very intentional with my book in most ways conceivable, and I’ve always treasured multidisciplinary art. I think every piece of art has the potential to dance with others in relationship, and it’s important to me that every piece of art I put into the world co-exists with others. Most presses have people who do the cover.

But I didn’t want just any amazing artist, I wanted my friends. The people I invited to collaborate on the cover and the interior images are not just artists who I know, but they’re people who know the sound of my crying. They didn’t just read the book and figure out how to portray the vibe—they already knew my vibe, and then read the book, and then took it a step further.

I also wanted people working on this with me who were also doing the work outside of this project—and by that I mean organizing. Both Angél Faz and Anna Jack Jackson live a life that strives to make the planet better for all blessed by the same sky.

As people read about your dreams for Earth in your book, what do you hope it will inspire in our own dreams for our planet and world?

I hope reading my book will help others think about ways they can make someone else’s day or life more joyful, more easeful. That might look like a parent talking to their son about consent, or a non-person of color talking to their children about race. I want to inspire people to be pre-emptive in their care—address possibilities for harm before they occur by talking about justice issues early. I also want folks to bask in their blessings.

Remember to really, really feel the kiss of the breeze and the warmth of the sunshine. Enjoy the weather while we can, try to hear the plants around you, hold the hands of those you love. Collective kinship: abolish borders and forget nationalism, love abundantly.

You can order a copy of ‘Dreams For Earth’ now, follow Fatima-Ayan on Instagram, subscribe to her Substack, and see more of her writing and activism on her website.