For fans of Kacen Callender, Lin Thompson, and Kyle Lukoff, comes a middle grade novel set in 1973 about a child who feels more boy than girl and is frustrated that people act blind to that when—except for her stupid hair and clothes—it should be obvious! ‘North of Tomboy‘ by Julie A. Swanson (SparkPress, Sept. 2) is based on the author’s own experience growing up in rural Leelanau Peninsula, Michigan in the 1970s and shows how rewarding being yourself can be.

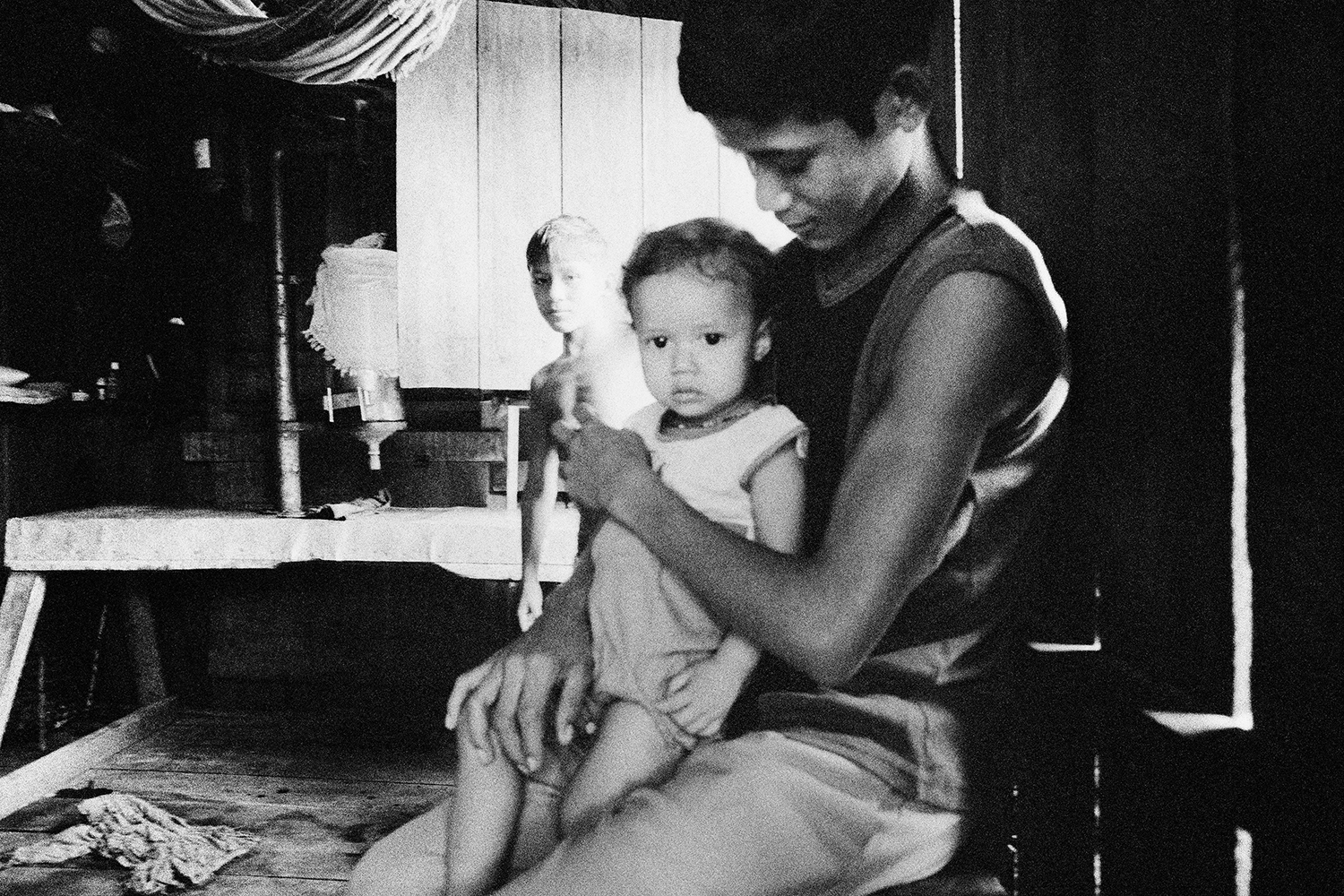

Shy fourth grader Jess Jezowski turns the tables on her mom when she’s given yet another girly baby doll for Christmas. This time, instead of ignoring or destroying it, she transforms it into the boy she’s always wanted to be—a brave, funny little guy named Mickey. Making him talk, Jess finally lets the boy in her express himself.

But when Mickey evolves to become something more like an alter ego whose voice drowns out her own and the secret of him escapes the safety of her family, Jess realizes Mickey’s too limited and doesn’t allow the boy part of her a big enough presence in the world. She must find a way to blend him into her—so she can be that side of herself anywhere, around anyone.

Jess tries to wean herself from the crutch of Mickey’s loud, comical persona, and to get her family to forget about him, but she struggles to do both. What will it take for her to stop hiding behind Mickey and get people to see her for who she truly is?

In anticipation of the book’s release this Fall, we were lucky enough to feature an excerpt from ‘North of Tomboy’ below, from the Prologue and Chapter 1.

Mishmash me, Jessica Jezowski

On the day I was born, God made a mistake.

It’s like he started making me out of blue clay: He used a big chunk for my body and a ball of it for my head. He pulled off hunks and rolled them into logs for my arms, legs, and neck. He pinched off pieces for my hands, feet, nose, ears . . .

But then he ran out right at the end and he needed some more to finish me. Only he didn’t see any more blue clay around, so he just grabbed a lump of red lying nearby.

The blue was boy, the red girl. He stuck the red on the blue for the final parts, smearing them together so that red and blue made purple, and you can’t tell where one color starts and the other stops.

I’m like a mishmash clay figure. In some spots you might still see streaks of red, but mostly I’m blue with purple patches. And inside I’m all blue.

I don’t know why God made me that way, but he did. And I mostly like how I am. Or I would if people would quit treating me like a stupid girl, expecting me to look and act like one. Because they might’ve named me Jessica, but I was supposed to be a boy. I’m way more boy than girl.

…

Vampire Boy, Zombie Girl

Christmas Eve 1972

Chip and I are right on Matt’s heels, but Matt slides to a hockey stop and puts his arms out. “Shh,” he says, “listen . . .” Over the scraping of our blades and the howling of the wind, a faint musical sound makes its way across the ice to us.

I push my hat up, uncovering an ear. Yup, the big bell on our deck Mom rings when she wants us to come home. She bought it when we moved up to Uncle JD’s. It worked so well that when we moved out of Cabin 5 and into our new house Dad built on the lake, we brought it with us. In the summer, the sound of it carries over the water and echoes off Sugarloaf, and we can hear it no matter where we are. But the snow blanketing the hills around the lake muffles everything.

We turn and skate for shore. Lucy opens the back door for us wearing nothing but underpants, her skinny first grade legs sticking out of them.

“C’mon, Jess. I got the boat and the shark.” She holds our bath toys out as the boys rush in past us. “The people are swimming already.”

Mom chuckles, helping me undo a knot in my lace. “I’m running a bath for you girls, but here . . .” She slides a stack of clean clothes off the dryer as I get up. “Take this to the boys’ room on your way.” She should’ve given it to them, but they were in such a hurry to check the score of the Packers’ game, they ripped their skates off and ran for the TV.

I set the clothes on Matt’s bed. His seventh-grade basketball jersey tops the pile. I hold it up, #33 just like his and Chip’s idol, the Milwaukee Bucks star, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

Stepping behind their door, I pull my sweater off, put the jersey on. It looks and feels great, loose and airy with big armholes that show your muscles. Flexing, I check my reflection in the window over their desk. Not bad.

I wish I could play a sport. That’s all I asked for this Christmas, to be signed up for one. Mom says there aren’t any for girls my age, but I bet she could find something if she tried. She teaches at an elementary school; she must hear about kids’ sports. And Glen Lake’s in the same county as our school. Fishtown probably has the same kinds of teams.

Before taking my pants off to try Matt’s shorts on, I listen for the boys. They get mad when they catch me in their stuff. As if I have cooties.

“Get a load of this box score.” Chip sounds like he’s on the couch. “The Bucks beat the Celtics and guess who had twenty-six points and thirteen rebounds? Our man Lew Alcindor!”

They can’t get used to calling him Kareem. Last year was his first season going by that, so it does sound weird. I still can’t believe he was Catholic like us before he converted to and took Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as his new, Muslim name. We don’t have Black people in our church. But then we don’t have any Black people in our school or in the whole county for that matter.

I guess there are Catholic Black people in New York City where Kareem grew up; he went to Catholic school and everything. I read all about him in that book up there on Matt’s shelf, ‘Big A: The Story of Lew Alcindor’.

Footsteps. Uh-oh. I pull my pants up, whip the jersey off, fold it. Grabbing my sweater, I head out the door without even putting it back on.

“Geez,” says Chip as we bump into each other, “you girls are always running around half naked!” He puts an arm up, shielding his eyes.

“Shut up.” Like I look any different than he does without a shirt on. Giving him an elbow, I push past him to the bathroom. Lucy and I test the water. It gets so much hotter in our new house than it did in the cabin.

My feet burn but, ahh, the rest of me . . . I’m freezing. Even before we went skating, I felt shivery. Since the minute I woke up, I’ve been blowing in my fists, shaking my arms, and jumping all around, buzzing with icicle-bones energy.

Today’s the best day of the year, even better than Christmas. After church, we go to Uncle JD’s and do all kinds of fun things and stay up late playing with our cousins. I’m glad we’re just one house over from them on the lake now instead of up the road in a cabin—or a whole state away like before that.

When my hair’s rinsed, I take the long waterfall of it hanging down and fold it over my head, back and forth on itself like that ribbon candy Mrs. Kirby gave us Friday at our class party. Then I smash it flat.

Lucy points at me, giggling with that toothless grin of hers. “You look like a boy.”

A smile springs to my face. “Don’t I?” With short hair, I’d pass for one. But thinking about that gets me mad at Mom all over again and my cheeks fall. By the time you’re in fourth grade, you should be able to have your hair the way you want it. I’ve asked Mom to cut my hair a million times. She says she likes it long, everyone does, it’s “spun gold” and girls would die to have hair like mine so why would I want it short? Blah, blah, blah.

But lately when I ask, she doesn’t even answer, just gives me a look like, Watch it, you’re trying my patience. Like asking again is being disrespectful and I’m just trying to irritate her. Which would be a sin, so I can’t.

After our bath, Mom wraps Lucy in her bathrobe, combs her hair, and sends her to go sit by the woodstove and stay warm. Then it’s my turn for another torturous detangling.

“Alright, boys,” Mom calls when she’s finally done scalping me, “the bathroom’s empty.” She hustles me out of it, steering me by the shoulders like a grocery cart to my room. “C’mon, Jess, let’s get you ready first. You’re the easiest.”

My eyes flip to the ceiling. Mom always tells people how I’ve gone from being her most difficult child to her easiest. She says it like she’s somehow responsible for my turnaround, or the move up here did me good, and either way it was great parenting decisions that did it. It did happen when I was six, but it wasn’t our move to Michigan that did it.

“And besides,” says Mom, “I have to get my angel ready. Don’t want to feel rushed about that. Here, slip this on, ma chérie.” She hands me the white gown she sewed. I never said I wanted to be in the pageant. Sister Sebastian just came in our catechism classroom, said she needed angels, and chose three of us.

“Wait until we get to church to put your wings and halo on. And I’ll put your barrette in once your hair’s dry.” Mom reaches over to lift up on the head of the fancy porcelain lady on our dresser. Her ball gown comes apart at one of the tiers in her long, full skirt. In the hollow skirt bottom are our barrettes and all Lucy’s ponytail holders.Mom fingers through them. “How about white today?”

I shrug. As long as it’s not pink or flowery and doesn’t have a bow on it. One simple barrette is the only thing Mom can put in my hair. She can’t do anything else to it. That’s the deal we made; if I have to have long hair, then at least I don’t have to wear it in ponytails, pigtails, or braids where hairs are always pulling and giving me a headache. A side barrette to keep my hair out of my eyes is it.

Mom slips the barrette in her bra. “There, now you just need tights. Why don’t you wear your boots, and we’ll bring these slippers with us. And how’d you like to wear the cross you got for your First Communion?” She goes over to my jewelry box, picks it out.

I can’t stand the way Mom asks how I’d like to; she knows how—not at all! But I shrug and feel myself fading, tuning out, marching over to her.

I didn’t always turn into Good-Girl Zombie like this. When I was little, I threw tantrums. Mom says I’d get so worked up I’d lose my breath and my lips would turn blue, and I’d pass out. I don’t remember passing out, but I do remember growling until my throat hurt and getting hot and sweaty, my whole face smeared with tears and snot.

Mom has no idea what it’s like for the boy in me. When she comes at me with jewelry or a dress, it’s like holding a cross up to a vampire. He can’t look at it. It hurts his eyes. He has to squint and back away. And when she puts it on me, it burns his skin and he writhes around in pain. The whole time she’s dressing me, it’s killing him, driving him away. It makes him crawl back in his coffin where it’s safe. He closes the lid and hides in there. I miss him then. I feel hollow and dull, just a shell of a girl on the outside. A zombie.

The boy writhing around used to look like a tantrum. But now he does it as he scurries back to his coffin inside me, and it’s shiver-quick, more of a wriggling away or a burrowing in than anything Mom can see on the outside. Even though I let her put things on me or put them on myself, I still feel like hitting, ripping, growling.

While she stands behind me trying to hook the clasp in the tiny ring at the end of the necklace, I hold my breath.

“There.” She pulls my hair back, comes around to give my arms a squeeze, and smiles. “Very good. Thank you. Now come sit by the woodstove and dry your hair while I help Lucy.” Mom drapes my tights over my shoulder, hands me my wings, gold tinsel halo, and slippers.

“Lucy, ma petite,” she calls, coming out into the open part of the house, “time to get beautiful. And, boys, we’ve only got five minutes. Dad’s out there shoveling and warming up his truck.” Dad’s Crew Cab pickup has four-wheel drive and a plow; any time it’s snowing, we take that instead of the station wagon. “Hop to it!”

The boys come out of their room dressed and ready to go. They’re only a year apart and the same height, but I can’t help noticing how different they look in their shirt-‘n-tie outfits. Thick Matt with honey-colored hair. Skinny Chip, the only one of the four of us who got Dad’s dark hair.

They head for the closet where we hang our church coats. Guess I better do the same. We all know how Dad gets if we’re not out there on time.

Ugh, my long wool coat. Compared to everyone else, we look like royalty marching into church. Here I come—Princess Jessica.

. . . With a vampire boy holed up in his coffin deep inside.

Julie Swanson grew up in Michigan’s “Little Finger,” the Leelanau Peninsula, where many of her stories are set, but has lived in Wisconsin, Iowa, New Hampshire, California, and Virginia. For the past twenty-five years she’s lived in Charlottesville, VA. Julie writes middle grade and young adult novels and enjoys sports, the outdoors, “making things” (almost any type of art or craft, woodworking), reading, writing, eating, planting trees, and spending time with family. Follow Julie on Instagram and Facebook, and connect with her on Linkedin.