When older generations die, and oral histories are not passed down for familial or cultural reasons, generations are left to piece together fragments, memories, ephemera, and family stories to create a picture of one’s own legacy.

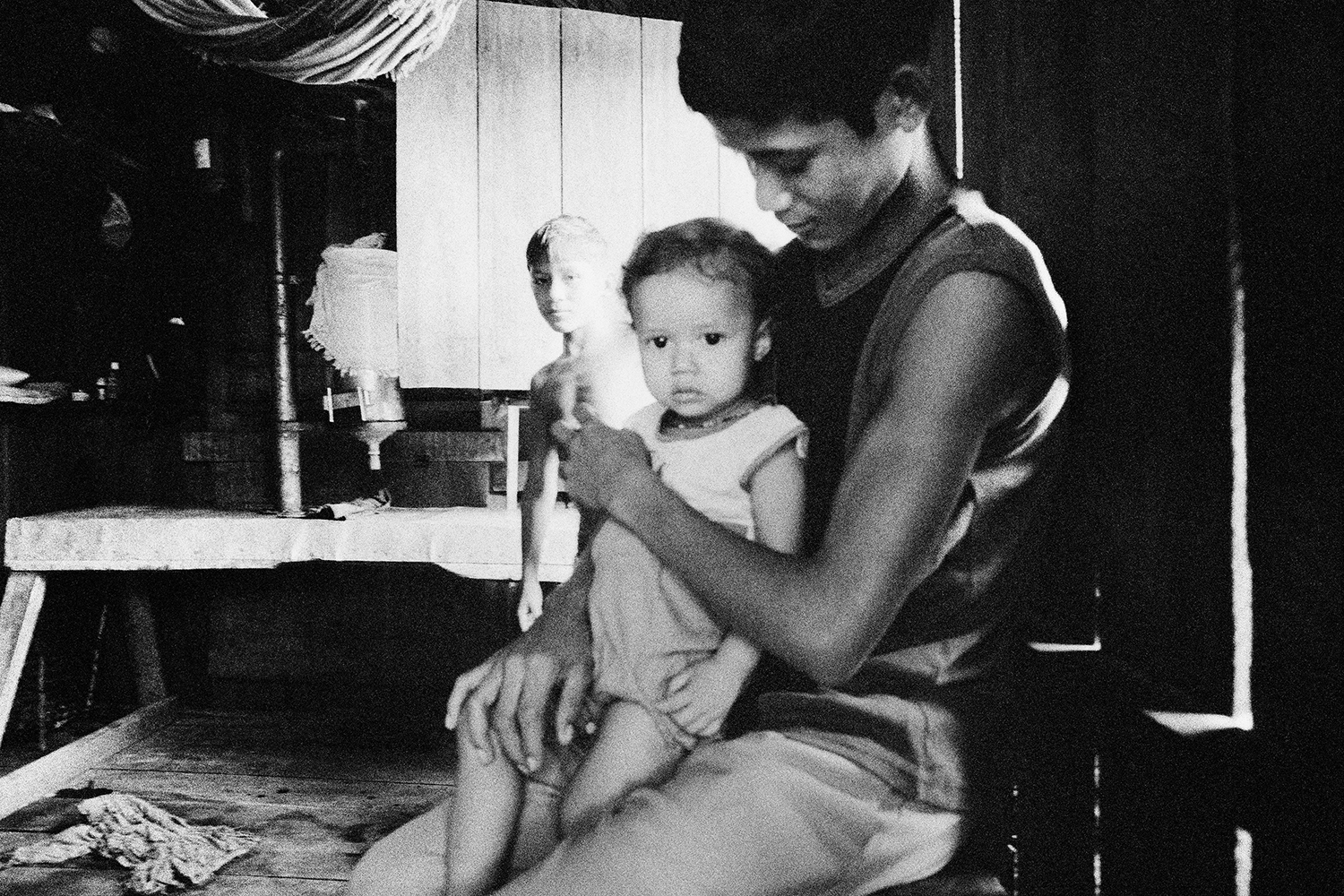

Photographer and multimedia artist Betty Yu, an award-winning filmmaker, socially engaged multimedia artist, photographer and activist born and raised in NYC, has released a new book titled ‘Family Amnesia: Chinese American Resilience’ (Daylight, Summer 2025) combines her photographs, her grandfather’s photographs, archival material, and mixed media collages to honor her own Chinese American family roots in the United States, as well as the Asian American immigrant experience and resistance in the U.S.

The book is divided into six sections, with each one highlighting a particular angle to Betty’s family historical arc. One focuses on her grandfather’s story, another on her grandmother, one on her mother and sister, while another one highlights the labor activism thread that runs through generations.

In ‘Family Amnesia’, Betty looks at a reclamation of a family and collective identity. Newspaper clippings and other historical documents combine with Betty’s photographs to provide visual and graphic flow to the book, while also delivering comprehensive insights into the political and social context of the timeframes within her family’s story. In addition, multi-image spreads of thumbnails from several short documentaries Yu made are also included, and serve a similar function, deepening the reader’s experience and knowledge.

Each film highlights a particular aspect of her family’s story. In one, she documents the impact to her family of sweatshop conditions her sister and mother experienced and their leadership in community organizing and resistance movements against the inhumane conditions in the United States. Her grandfather was also a labor organizer, and in another film with image spreads in the book, she writes about documenting her exploration of her grandfather’s “radical history as a labor organizer and cofounder of the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance of New York.”

The book includes essays written by Betty to allow the reader an in-depth look into her process for creating the book, how her own family history shaped the final version, as well as considerations of geopolitical factors informing life within a framework of harmful western ideology and perceptions.

The book concludes with a timeline spanning 1785-2021, highlighting key historical events and providing in-depth scaffolding within which her own family story exists.

We had the opportunity to speak with Betty about her insightful book, and what she hopes will impact readers the most when they see her photographs, collages, and read her essays.

What was your creative process in collecting the photos and compiling them for your new book?

The creative process was pretty fluid for me. Over ten years ago, I found hundreds of photographs belonging to my grandfather. They span his life, starting in the 1920s in Chicago, to his military service during WWII, to becoming a labor organizer, to the U.S. reunification with my grandmother in the 1940s, to the end of his life in the 1980s.

His life is still an enigma to me. I was both surprised and excited to find photos of him as a leader with the New York Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance (CHLA) – a pivotal group fighting for the labor rights of hand laundry workers – founded in 1933.

Back in 2011, I made a short film entitled “Discovering My Grandfather Through Mao” that centered my grandfather’s photo archive and his leadership in CHLA. It wasn’t until the 2020 Pandemic COVID lockdown period – that I really had a chance to sit with all of my grandfather’s archives as well as my immediate family’s photographs from the 1970s to the 1990s.

I was very disturbed by the heightened COVID-related anti-Asian violence and xenophobic sentiments. This really harkened back to the period of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. I really thought about how my grandfather survived those times in the US, from his time in Nevada to New York.

Since these photographs were taken way before my family and I were born I had to think deeply both in terms of the integrity of the content and stories that the photos held, as well as the quality of the photos themselves, I thought about the composition, aesthetic features and how they would fit into the larger narrative that I was trying to tell about my grandparents and the Chinese American experience during the 1920s to the 1950s.

And as I started to create collages with images of my grandparents and images that they took, I realized I was constructing my own version of the history I believe they lived through. And it was only natural to include myself, my family and my parents in these collages as well. Because even though there might have been a 40+ year gap between their experiences, in many ways the struggles that they’ve endured are very similar.

My grandparents worked in the hand laundry business and my parents worked in garment factories – both for very little pay for long hours under tremendous exploitation and racial discrimination – just to eke out a living. Of course as we know living and working conditions are very similar today for millions of immigrants.

As I was creating colleges and deciding on photographs to include – I constantly returned to the central question:

How do I preserve and pass on these stories of struggle that my ancestors wanted me to forget?

For the four generations of my family, survival itself was and is an act of resistance. What was it like for my grandparents, my ancestors in the United States? What were their dreams? How did they stay resilient while facing racism on a daily basis? Working with these photographic archives have brought me closer to unpacking the Chinese diasporic experience through my family’s personal lens.

How has multi-generational storytelling become a source of empowerment for you in our current political times?

Through the creation of these mixed-media collages I am reclaiming not only my family’s narrative, but our broader collective memory. The book is an act of fighting the cultural, social and political erasure of not only four generations of my family in the U.S. but paying homage to the hundreds of thousands of Chinese Americans who share similar experiences. Bringing our stories to the foreground is an act of resistance. This book is this act of resistance and love.

The meditative process of creating these collages has been healing medicine. Of course these are my own reimagined memories based on orally passed on stories and limited knowledge of my grandparents daily lives. But these works aim to highlight joy and resilience in the face of adversity. They interweave the realities of displacement, dispossession, nativism, labor exploitation and colonization (in Hong Kong) which have profoundly affected my family.

The role of storytelling has never felt more palpable. It has allowed me to reconstruct the pieces, the fragments, and the stories – assembling a more holistic narrative of my family. These forgotten stories not only honor my ancestors’ past, but also allow me to live in the present.

What are some of the key historical moments your images portray throughout the book, and what memories did they trigger in you as you put them together?

Some of the key historical moments and periods that the engages with is the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the founding of the Chinese Hand Laundry Alliance of NY in which my grandfather was a co-founder of, WWII and the anti-facism movement, communist movements in the U.S. in the 1950’s, McCarthyism, and labor rights organizing and anti-sweatshop activism in NYC’s Chinatown in the 1990’s.

My family was deeply impacted by each of these historical moments and periods I explore in the book through collages, photographs and words. My most vivid members are my sister, mother and I, organizing side by side with other Chinese women – mainly low-income garment workers to demand an end to inhumane working conditions.

From my sister going on hunger strike to my mother risking being blacklisted by the garment industry – I treasure those critical moments. We were part of making history – immigrant Chinese workers were standing up for themselves, this led to profound changes and improvements in the industry.

By piecing together fragments of memories and images of family members, what were some of the missing pieces of the story you were able to construct? For instance, did you ever discover what your grandparents dreamed about?

This is really hard to answer because a lot of the stories I hold about my grandparents and grandparents were verbally passed on. And you can say my collages are based on what would be considered ‘conjecture’. But throughout the course of making this book I was able to work with my parents and ask them lots of questions, their answers lead to more questions, which lead to more answers.

And I was able to dig much deeper into these complex narratives and sometimes an unlocked memory would lead to a dead end or an open one with no definitive answer. Before my dad passed away in 2024, I learned a great deal about my great grandfather – he worked in Reno, Nevada in the late 1870’s and his money earned helped build their family house back in Toisan, China.

Through dialogue and examining my grandpa’s photos more deeply, I was able to track down his military service during WWII as a volunteer and his immigration records of his landed vessels in San Bruno, California. And of course this was all during the Chinese Exclusion period and only male merchants with money could immigrate.

His immigration records showed that in order for him to work in the U.S. he had to prove that he had an immediate family member – his father in the U.S. – and two white witnesses had to vouch for him. In fact what we know as ICE today and the concept of immigrant border control was originally designed to limit and surveil Chinese immigration to the U.S.

What kind of comfort or encouragement do you hope “Family Amnesia” will bring to other Chinese American families today?

As a Chinese American, I hope this book is engaging and thought-provoking. I hope it inspires other Asian Americans and viewers to reflect on their own role in society and to see themselves as agents of change. I hope the book encourages and emboldens the Asian-American community to speak out against anti-Asian racism and to support broader racial and social justice movements.

What message do you hope will land with other readers as they learn about your family story and your experiences?

I hope their takeaway is that we remember every person, every family, every community has a story that is infused with struggle, joy, resilience and resistance. And especially the stories of traditionally marginalized communities, like my own, who are often overlooked, underrepresented and dismissed – are equally as important.

In fact, now more than ever – it’s vital that immigrants, people of color, low-income, the LGBTQIA community – speak out and demand our stories be heard. We see how the Trump administration has systematically attacked our communities – stripping us of our basic civil and human rights. His cruel and heartless policies and actions have real life and death consequences.

What role do you want ‘Family Amnesia’ to play in our current sociopolitical climate, and how do you hope it will contribute to contemporary conversations around immigration, racism, family, and history?

The heart of this book was created during the heightened attacks on Asian Americans, racial justice uprisings, and the Movement for Black Lives – and now our basic human and civil rights are being unconstitutionally taken away from us by this right wing fascist Trump administration – there has never been a more critical moment for artists like me to connect to audiences through our work and deepen our impact. I continue to challenge myself and to push the boundaries of how art can truly help shift the nation’s consciousness and change hearts and minds.

I hope that readers see a timeless value in the book. It is not necessarily bound to a particular time period. It’s not only about the Chinese American experience. It’s not just about struggle and hardship, but it also celebrates the joy of living and the joy in resistance.

These are universal experiences and I hope readers can connect to the images and stories in an organic way where they see a reflection of themselves.

You can order a copy of ‘Family Amnesia: Chinese American Resilience’ out now from Daylight books. See more of Betty Yu’s work on her website, and find links to her appearances and exhibits on her Linktree.