By Anna Monardo

I got married at 39 ½, had two miscarriages by 40, divorced at 41. Finally, at 42, I was ready for the biggest step of my life: I began my application to adopt a baby from Vietnam. The decision to become a single mother hadn’t been difficult. I’d always known that my life wouldn’t make sense to me if I missed out on raising a child. But the decision to adopt—that hadn’t been easy.

One stumbling block I had with adoption was the intimacy of it. Blunt truth: I was afraid another woman’s child might be too other. While holding her baby, would I search for the mother’s secrets in the baby’s face, or would I long for the details of my family’s features? And what if I couldn’t cozy up to the scent of a stranger’s child? Would I be ready when it was time to lift my baby from the bedding and cloths—possibly dirty, soiled—he or she had been kept in? I was ashamed of my squeamishness, but I had to admit it to myself. How else could I figure out if I was capable?

When my adoption agency offered a weekend workshop on attachment, the opening discussion was about loss. The agency director, Cheryl, told us, “For babies who are adopted, life has not taught them consistency.”

Even for babies who, just minutes after birth, land in the arms of eager adoptive parents or attentive foster parents or conscientious caregivers, there is the staggering loss of the birth mother’s body and voice. In utero, the baby lived for months hearing that voice, and now it’s gone. For babies in orphanages, there may or may not be timely feedings. The baby might be held and spoken to during feedings, or the bottle might be propped.

And in time, whether the orphaned baby receives excellent care or negligent care, there will be one more unpredictable rupture when the baby is taken from the now-familiar atmosphere of the orphanage and put into the arms of the adoptive parents. If those parents are from a different culture, the baby may no longer hear their native language—one more loss. The new parents’ voices make strange sounds; their scents are an onslaught of the unknown. The adopted baby experiences incalculable losses and changes, each one as unpredictable as an earthquake.

“Think of the five most important things in your life,” Cheryl prompted us. I listed my health, creativity, family, friends, and home. “Now, cross out one of them,” Cheryl said. “What would it be like to lose that?” We all sat quietly, no one looked up. “Now cross out another of your five important things.” And she continued until we had crossed off everything we cherished. “That’s how the world feels to an adopted baby. That baby has lost everything.”

By now, within me, the paradigm shift had happened. All I could think about was how strange and terrifying the sound and size and scent of the adoptive parent must be for the baby. What would I do to soothe that baby? Anything in my power.

The university where I taught granted “a period of eight weeks paid disability leave (pre-and postpartum) for absences associated with pregnancy and childbirth,” so I submitted a request for eight weeks, which my department and dean approved. But a few weeks later, someone in an admin office called me to say that as an adoptive mother, I did not qualify for parental leave, which was considered disability leave. There was no disability associated with adoption. For adoptive parents, a two-week leave was granted “to provide care and assistance to the child.”

Two weeks? The round trip to Vietnam and back would take that long or more. And what about time for the all-important attachment process?

“This policy is saying that my adopted child is less deserving than a birth child,” I told my dean.

By now, I was 44 and tired. For over two decades, I’d been carving a life far from what my traditional Italian family had expected. After college, I’d left home to work in New York City and live on my own. I’d left the nine-to-five work world to teach, which gave me summers free to write my novels—and in time, I hoped, to spend summer days with my kids.

I want to raise a child. In my family’s eyes, I had at times seemed radical, but at heart I was a traditionalist. I was not taking motherhood or adoption lightly. My adoption agency had educated me: I knew what my child needed. I was crying when I said to my dean—I trusted her enough to cry in front of her—“Adoption is not a second-class family experience.”

“Your child is not less deserving. You do need to get that leave.”

I had good people in my corner, but this was my fight to fight. I put aside the manuscript I was working on, and my parental leave campaign became my summer’s work. I met with or sent letters to state senators, members of the university’s Board of Regents, university lawyers and private lawyers, my on-campus union rep, psychologists, social workers, medical doctors, news reporters, and colleagues across campus who had recently become parents. I asked a pediatrician, “Do you think an adopted baby requires the same parental-leave time as a birth child?”

“No,” she said, “the adopted child needs more time.”

And then finally, one sunny day in my office, I got an email with the good news that the Regents had “expanded the university adoption leave policy for faculty and staff,” granting the primary caregiver for an adopted child up to eight weeks of leave, equal to the time granted to birth parents. This new policy applied to both female and male employees. The bylaws had been changed for the entire system, which included four campuses.

Several of the administrators I’d talked with during my campaign sent me emails and personal notes to say they were pleased with the results, and they gave me their best wishes.

Now my son is college age and finishing his degree on the campus where I’m about to retire. Twenty-seven years: I’ve had a good run in my classroom, but I’m especially glad I can walk away knowing that that bit of legislation in support of adoptive families is solidly in place.

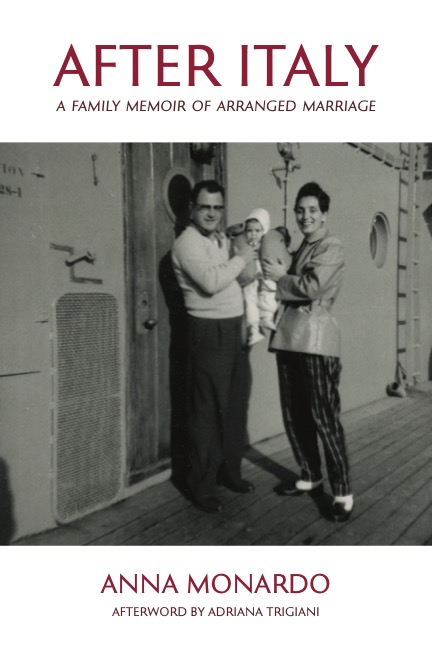

Anna Monardo grew up in Pittsburgh, with strong ties to her Calabrian family. Her memoir, ‘After Italy: A Family Memoir of Arranged Marriage’, forthcoming with Bordighera Press in May 2024, is the story of her family’s immigration to the U.S. ‘After Italy’ is the factual retelling of the family story at the heart of Monardo’s first novel, ‘The Courtyard of Dreams’ (Doubleday). She teaches in the Writer’s Workshop at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. Learn more at annamonardo.com